Introduction: Recording Formats and Strategies

“Anthropologists are those who write things down at the end of the day”.

(Jackson, 1990, p. 15)

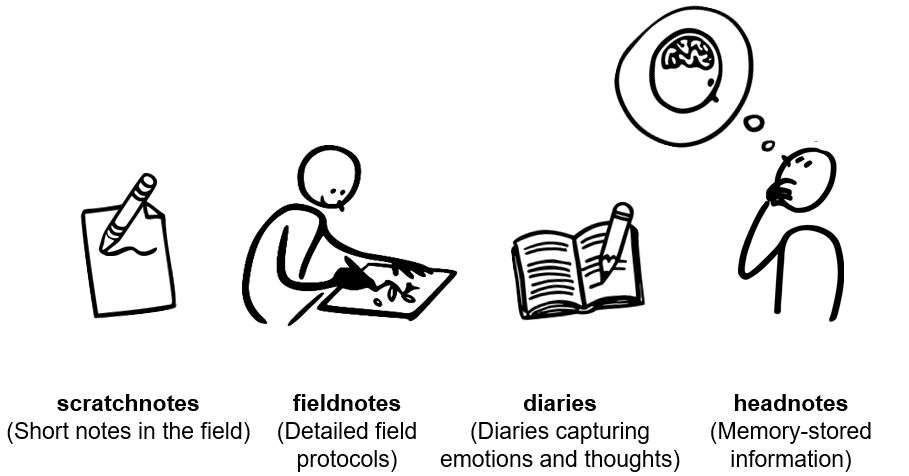

This section addresses a central aspect of social and cultural anthropological recording strategies: the creation of field notes and their subsequent daily elaboration, typically in the evenings, into detailed descriptions of the day’s observations, experiences, and inquiries. Short, keyword-based notes, often handwritten in notebooks and serving as memory aids for ethnographers, are typically expanded into extensive research protocols spanning numerous pages. In English-language literature, these research protocols derived from brief notes (scratchnotes, jottings) are commonly referred to as “fieldnotes” (Sanjek, 1990, pp. 97). Fieldnotes are chronological, which facilitates reconstructing the research process during analysis. Ideally written daily, they typically contain diverse information about social life, which is later synthesized into meaningful units during analysis. In this sense, they can be seen as the „pretext for ethnography“ (Lederman, 1990).

Many researchers also keep personal diaries, documenting their experiences and emotions. However, many report difficulty in separating these formats, leading to intertwined entries. As a result, personal emotions and perceptions are often embedded in research protocols, while ethnographic descriptions find their way into diaries. Importantly, social and cultural anthropologists produce these three core textual formats – scratchnotes, fieldnotes, and diaries – primarily for themselves, meaning they are decipherable only by the authors (Lederman, 1990, p. 72). This self-referential nature raises concerns among ethnographers about how open-science demands may significantly alter their recording routines by introducing potential secondary users as an imagined readership, thereby profoundly changing the nature of fieldnotes (see also the article Data in Ethnographic Research).

In addition to these three textual formats, “headnotes” – information stored in memory – also play a significant role. These implicit, unrecorded insights, accumulated during research, are invaluable for interpreting research documents and materials:

„We come back from the field with fieldnotes and headnotes. The fieldnotes stay the same, written down on paper, but the headnotes continue to evolve and change as they did during the time in the field.”

(Sanjek, 1990, p. 93)

This underscores the importance of memory-stored information, which, despite not being recorded, plays a critical role during analysis and the writing of ethnographic texts (see also Fabian, 2011). Scratchnotes and headnotes are particularly vital in situations where no formal recording – on paper or digitally – is possible, requiring researchers to rely entirely on their memory for later documentation.

Source: Text formats in ethnographic research, Anne Voigt with CoCoMaterial, 2023, lizenziert unter CC BY-SA 4.0

As an example, reference can be made to the research conducted by Meike Meerpohl on Trans-Saharan trade in Chad between 2003 and 2007, which was affected by the violent Darfur conflict and thus marked by numerous politically sensitive situations during which immediate note-taking was impossible, necessitating that much of the data had to be recorded retrospectively from memory. Meerpohl reports frequently encountering deep-seated mistrust, which made open note-taking during conversations, the use of recording devices, and the open mapping of local market structures impossible, so that much had to be documented afterwards (Meerpohl, 2009, p. 32). She attributes the skepticism toward foreigners prevalent in Chad to the prolonged civil war, the French colonial rule, and a repressive state (Meerpohl, 2009, p. 35). Similarly, during her participation in a 1,000 km desert crossing with a camel caravan, the researcher was unable to maintain regular daily notes or conduct extensive interviews, as she was simply too exhausted in the evenings after 12 to 15 hours of camel riding (Meerpohl, 2009).

Even in less challenging field contexts, the insights gained through participant observation can only be recorded retrospectively, although this is usually done without significant delay to minimize forgetting. The limits of documentation are particularly evident in the numerous multisensory impressions researchers gain during participant observation. These can only be partially verbalized and largely remain in the embodied memory of the researchers.

Literature

Fabian, J. (2011). Ethnography and Memory. In Melhuus, M., Jon P. Mitchell, J. P. & Wulff, H. (Eds.) (2011). Ethnographic Practice in the Present. New York. Berghahn.

Jackson, J. E. (1990). ‘‘I Am a Fieldnote’’: Fieldnotes as a Symbol of Professional Identity. Sanjek, R. (Ed.). (1990). Fieldnotes: The Makings of Anthropology. Cornell University Press. https://doi.org/10.7591/9781501711954-002

Lederman, R. (1990). Pretexts for Ethnography: On Reading Fieldnotes. In Sanjek, R. (Eds.). (1990). Fieldnotes: The Makings of Anthropology. Ithaca. Cornell University Press.

Meerpohl, M. (2009). Kamele und Zucker. Transsahara-Handel zwischen Tschad und Libyen. Dissertation, Universität zu Köln https://kups.ub.uni-koeln.de/3263/1/DissertationMeerpohl.pdf

Sanjek, R. (Eds.). (1990). Fieldnotes: The Makings of Anthropology. Ithaca. Cornell University Press.