Rights and Licenses

Introduction

Throughout the research process, researchers may encounter legal questions regarding their research data'Data that are a) created through scientific processes/research (e.g. through measurements, surveys, source work), b) the basis for scientific research (e.g. digital artefacts), or c) documenting the results of research, can be called research data.This means that research data vary according to projects and academic disciplines and therefore, require different methods of processing and management, subsumed under the term research data management” (Forschungsdaten.info, 2023). Read More, involving various legal areas such as copyright lawThe German Copyright Act (UrhG) protects certain intellectual creations (works) and services. Works include literary works, photographic, film and musical works, as well as scientific or technical representations such as drawings, plans, maps, sketches, tables and plastic representations (§ 2 UrhG). The artistic, scientific achievements of persons or the investment made, on the other hand, are considered to be services worthy of protection (ancillary copyright).The author is entitled to publish and utilize the work. Read More, related rights, data protectionData protection includes measures against the unlawful collection, storage, sharing, and reuse of personal data. It is based on the right of individuals to self-determination regarding the handling of their data and is anchored in the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), the Federal Data Protection Act (Bundesdatenschutzgesetz), and the corresponding laws of the federal states. A violation of data protection regulations can lead to criminal consequences. Read More, or data securityData security encompasses all preventive physical and technical measures aimed at protecting both digital and analog data. Data security ensures data availability and safeguards the confidentiality and integrity of the data. Examples of security measures include password protection for devices and online platforms, encryption for software (e.g., emails) and hardware, firewalls, regular software updates, and secure deletion of files. Read More1See the list of relevant legal areas in research data management from Humboldt University of Berlin: https://www.cms.hu-berlin.de/de/dl/dataman/teilen/rechtliche-aspekte/rechtliche-aspekte.

Source: Relevant legal areas in Research Data Management, Anne Voigt with CoCoMaterial, 2023, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

At the latest, when publishing, archivingArchiving refers to the storage and accessibility of research data and materials. The aim of archiving is to enable long-term access to research data. On one hand, archived research data can be reused by third parties as secondary data for their own research questions. On the other hand, archiving ensures that research processes remain verifiable and transparent. There is also long-term archiving (LTA), which aims to ensure the usability of data over an indefinite period of time. LTA focuses on preserving the authenticity, integrity, accessibility, and comprehensibility of data. Read More, or potentially reusingData reuse, often referred to as secondary use, involves re-examining previously collected and published research datasets with the aim of gaining new insights, potentially from a different or fresh perspective. Preparing research data for reuse requires significantly more effort in terms of anonymization, preparation, and documentation than simple archiving for storage purposes. Read More research data, questions must be answered, such as (Forschungsdaten.info, 2023j):

- Who owns the research data?

- Are the research data protected by copyright? If yes, which ones?

- Are third-party rights, such as data protection or personal rights, affected? If so, is consent and possibly usage permission required?

- What should be considered when sharing and archiving research data?

- Under what conditions may research data be reused?

- Which license is most suitable for this purpose?

These aspects form the basis for the legal publication and reuse of data, as the use of copyrighted works by third parties requires the consent of the respective rights holders. This permission can be granted through a licensing agreement, which regulates the usage conditions.

If personal references are identifiable in research data, additional legal areas such as personal rights or data protection (see the article on Data Protection) are involved. In this case, the personal reference must be removed (see the articles on Anonymization and Pseudonymization) and/or explicit consent from the affected individuals must be obtained (see the article on Informed Consent).

Research Data and Copyright (UrhG) as well as Related Rights

The question of whether research data are protected by copyright is not straightforward, as they are not inherently protected. According to prevailing legal opinion, a work enjoys copyright protection if it constitutes the intellectual creation of a person (author) (§2 UrhG), such as literary works, photographs, films, musical works, and scientific or technical representations like drawings, plans, maps, sketches, tables, and 3D models. Therefore, research data can also be protected by copyright if they meet the necessary threshold of originality, individuality, and creativity.

Raw data, such as bibliographic data, weather data, or other measurement data commonly collected in natural sciences, generally do not enjoy copyright protection. However, if such data are described, interpreted, and analyzed by a researcher, the elaborated text or graphical representation may fall under copyright protection if it reaches the required level of creativity. Whether this is the case must be assessed individually for each scenario.

Databases may also be protected as works if the contained data are arranged, systematized, and compiled in a specific way, representing a creative achievement. The individual data themselves are not protected. However, the creation of the database is generally protected by database producer rights (Klimpel, 2020, p. 32). In this case, related rightsRelated rights are ancillary rights under copyright law. They do not protect the work itself but rather the artistic or scientific performance of individuals or an investment made. This applies particularly to the creation of databases or the production of films. An artistic or scientific performance could include a theater performance, a translation of a work, or the creation of an image, such as a photograph or an X-ray. Read More apply, granting the database producer the right to assign exploitation rights.

Related rights protect the efforts of individuals when, for example, they edit or perform a work or create a photo that is not protected as a work. They also protect companies' investments, such as film production or publishing. This right acknowledges scientific, artistic, or entrepreneurial achievements as such (Wünsche et al., 2022, p. 31).

For research data in social and cultural anthropology (see the article on Data in Ethnographic Research), it can generally be assumed that they are subject to copyright protection, as they often involve qualitative research data such as excerpts, notes, observation protocols, and field diaries – where the threshold of originality can typically be considered met. Interviews and their transcripts may also be protected by copyright, with all involved parties – interviewers and interviewees – potentially holding copyrights to the data (Klimpel, 2020, p. 26). Related rights may also apply to photographs, databases, or videos.

The author holds the right to publish and exploit the work. While copyrights are non-transferable, usage rights can be assigned. If multiple authors have made creative contributions to a work, they are considered co-authors. In this case, usage rights can only be granted jointly, and conditions for reuse must be established collaboratively.

(Lauber-Rönsberg et al., 2018, p. 3)2Translated by Saskia Köbschall.

Research Data and Personal Rights

General personal rights are fundamental rights designed to protect individuals from (state) interference in their private lives. In research contexts, the right to informational self-determination – regulated under the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) – is particularly important (see the article on Data Protection).

In research, the right to one's own image can also be relevant, considered a special form of personal rights. It states that every individual has the right to decide whether and where their image is published. For the distribution and publication of photos or videos featuring identifiable individuals, explicit consent from the depicted person is required under §22 of the Art Copyright Act (KunstUrhG), both for print and digital media3See the

legal text here: https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/kunsturhg/__22.html.

Research Data and Usage/Exploitation Rights

If authorship is clearly established, the UrhG (Copyright Act) assigns the rights to publish, exploit, reproduce, distribute, and perform the work to the rights holder (§12 ff UrhG). However, usage and exploitation rights can also be granted to third parties, typically through a licensing agreementIn a license agreement or through an open license, copyright holders specify how and under what conditions their copyrighted work may be used and/or exploited by third parties. Read More in which rights holders specify which rights are transferred and how the work may be reused and exploited.

There is a distinction between commercial and open licenses:

Commercial licenses are often granted to publishers, allowing them to exploit the work, potentially for a fee. The broadest form is the total buy-out license, which grants unrestricted, exclusive, and transferable usage rights (Klimpel, 2020, p. 23).

Open licenses allow anyone to reuse a work freely under the conditions set by the license. Standardized open license forms, such as the widely used Creative Commons licensesCreative Commons licenses are pre-formulated license agreements created by the non-profit organization Creative Commons, allowing copyright holders to grant public usage rights to their creative works. Once a work under a CC license is used by third parties according to the terms of the license, a contract is established (TUM, 2023, p. 5). Read More (CC licenses), are considered licensing agreements. These pre-formulated contracts, provided by the non-profit organization Creative Commons, enable rights holders to grant the public usage rights for their creative works.

These licenses are easy to understand due to their standardized modular structure, legally valid internationally, and machine-readable, with over 2 billion CC-licensed works globally (Creative Commons, 2023a). They promote a culture of sharing and reuse and support the Open AccessOpen Access refers to the free, costless, unrestricted, and barrier-free access to scientific knowledge and materials. For third parties to reuse these materials legally, the creators must grant usage rights through a licensing agreement. Free CC licenses, for example, specify exactly how data and materials may be reused. Read More movement. If research data are to be made openly available, these licenses are recommended as they are legally secure, require minimal administrative effort for both licensors and licensees, and are globally recognized. As soon as a CC-licensed work is used under the terms of the license by third parties, the contract is considered legally binding (TUM, 2023, p. 5). If no license is granted, parts of a work can only be used within the scope of quotation rights or for one's own scientific research (§60c UrhG) (Brettschneider et al., 2021, p. 9).

In principle, it may be the case that, within the framework of employment relationships, "the creation of copyrighted works is part of the contractual duties or central tasks of an employee" and is contractually regulated (Lauber-Rönsberg et al., 2018, p. 7). In this case, the usage rights are granted to the employer (§43 UrhG) and not to the author. This often applies to academic staff when they create works under instruction (keyword: supervisors) as part of their duties. However, if research data are generated independently within the framework of the researcher’s own work, this regulation does not apply. Additional restrictions may arise from contractual agreements in research projects funded by third parties (Kreutzer, T. & Lahmann, H., 2021, pp. 35). Nonetheless, authors always retain the right to be credited.

Motivation

Compliance with legal requirements is part of good scientific practiceGood scientific practice (GSP) represents a standardized code of conduct established in the guidelines of the German Research Foundation (DFG). These guidelines emphasize the ethical obligation of every researcher to act responsibly, honestly, and respectfully, also in order to strengthen public trust in research and science. They serve as a framework for guiding scientific work processes. Read More. As stated in Guideline 10:

"Researchers should, where possible and reasonable, establish documented agreements regarding usage rights at the earliest possible stage of the research project. ... The usage rights belong, in particular, to the researcher who collects the data."

(GWP, 2022, p. 17)

To grant usage rights, it must be unequivocally clear that the work is protected by copyright. Since this can often only be determined on a case-by-case basis, it is important to address this issue early on and clarify whether there are any co-authorships. It is also in the researchers' own interest to have an overview of the topic in order to assert their own copyrights – especially for works created in project teams (co-authorship).

Furthermore, legally secure data are essential for the publication and archiving of research data, as appropriate licensing is a fundamental prerequisite for reuse by third parties. This is especially true when copyrighted works of third parties, such as images, are incorporated into one's own work.

The use of open licenses, such as Creative Commons licenses (CC licenses), enables simple, standardized, and legally secure licensing agreements, facilitating low-threshold, free licensing and reuse. Moreover, such licenses do not involve the exclusive transfer of exploitation rights, allowing researchers to continue working with and using their research data. Open licenses promote the sharing of research data and thereby increase the visibility of researchers and their work.

Methods

Clarifying Rights

Legal questions to be clarified (if necessary, consult legal departments, data protection officers at research institutions, review contracts, etc.):

Regarding Copyright and Exploitation Rights

- Are the generated research data considered "works" with sufficient originality, thus enjoying copyright protection?

- Are the research data possibly protected by related rights?

- Who is the author? Are there other individuals who contributed to the work and thus have co-authorship?

- Are there contractual stipulations from funding institutionsFunding institutions are organizations that provide financial support for scientific research, such as foundations, associations, or other entities. Internationally, most of these institutions have established guidelines for research data management (RDM) in research projects, meaning that potential funding is tied to specific requirements and expectations for handling research data. Some of the most well-known funding institutions in German-speaking countries include the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF), the education and science ministries of the federal states, the German Research Foundation (DFG), the Volkswagen Foundation, the Austrian Science Fund (FWF), and the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNF). Read More or other third-party funders?

- Were the research data generated independently or under instruction?

- Are the researchers employed, and is the creation of works part of their employment contract, or are there other contractual provisions? Do the usage rights transfer to the employer?

- Are there general regulations at the research institution regarding authorship for works created within the framework of employment?

- Are there model contracts at the research institution for granting usage rights?

Regarding the Rights of Third Parties (Copyright, Data Protection, and Personal Rights):

- Are personal data processed in the research data? Has consent been obtained from the affected individuals? Are the data anonymized? (See articles on Data Protection, Informed Consent, Anonymization and Pseudonymization)

- Do the research data contain copyrighted content from third parties? Have usage rights been obtained for this content? Or are these contents under an open license, and is it compatible with the planned license for the research data? Are the licensing details correctly indicated according to the license conditions?

- Are there images or videos in the research data showing identifiable individuals? Has consent been obtained from these individuals for publication and distribution? Or have the individuals been removed or obscured (using filters)?

Licensing

Excursus: Creative Commons Licenses

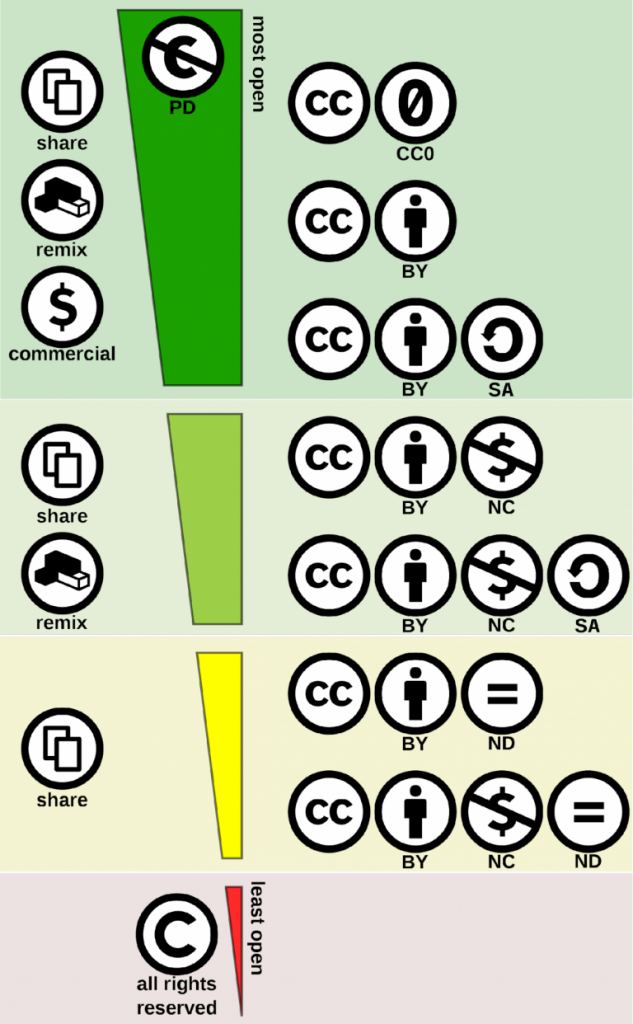

Creative Commons licenses are widely used, standardized licensing agreements composed of different building blocks. Each block specifies a condition for reuse, visualized with symbols, which are highly recognizable, enabling re-users to quickly understand the applicable conditions.

RIGHTS

BY Attribution – The name of the author must be credited.

NC Non-Commercial – The work may not be used for commercial purposes.

ND No Derivates – The work may not be altered.

SA Share Alike – The work may only be shared under the same conditions (license).

Source: Creative Commons-Lizenzen, Shaddim licensed under CC-BY-4.0

The globally valid licensing agreements are formed from these building blocks: CC0, CC BY, CC BY-SA, CC BY-NC, CC BY-NC-SA, CC BY-ND, and CC BY-NC-ND.

- CC0 represents a waiver of copyright.

- CC BY is an example of a very open license.

- CC BY-ND is more restrictive as the work may not be modified.

When material offered under a CC license is used in another work, the CC license of the new work depends on the original material’s license, and different license variants may not be compatible (Klimpel, 2019). For example, if a photo published under CC BY-SA is used in an article to be published under CC BY, the exact license of the article must also be CC BY-SA.

For the publication and archiving of research data, a specific CC license cannot be recommended in general, as contractual agreements, the type of data, their origin, and (potentially sensitive) content determine the appropriate license on a case-by-case basis. However, for academic text publications, the CC BY license has already become established and is recommended by the DFG (DFG, 2014).

Selecting the Appropriate CC License

To select the appropriate license, the licensing party must answer the following questions:

If no other CC-licensed materials are used:

May my work be modified? If yes, may the modifications be shared? If yes, under the same conditions? Is commercial use of the work permitted?

When Using CC-Licensed Material:

Under which license is the material published? Is this license compatible with my intended license, or does it determine the license for my work?

License Indication in Publications

In general, (CC) licenses should include (TUM, 2023, pp. 6):

- The name of the license

- The license version (if multiple versions exist, e.g., CC 3.0, 4.0…)

- A link to the license or license text

- If applicable, the logo/image associated with the license

Practical Example

License Indications When Using Third-Party Works in One's Own Work:

For mixed works with heterogeneous licenses, licensing information must always be placed directly on the work, such as the license information, source/author, and license link in the caption of a protected image.

Practical Example

Source: Collaborative work 1, Cocomaterial licensed under CC 0 1.0 4According to the license, attribution of the authors is not mandatory for this image; however, it is advisable to cite the source to ensure legal security and to honor the authors.

Even for self-created visual material that shares the same license as the overall work, it is recommended to include the source and licensing information directly on the visual material.

Practical Example

see: Guide

Practical Examples

Here are three different application examples of publications, each showing varying indications of authorship, licenses, and licensing details (click the link for more information).

Example 1: Various Examples of Publications

- Röttger-Rössler, B. & Franziska Seise, F. (2023). Tangible pasts: Memory practices among children and adolescents in Germany, an affect-theoretical approach. Ethos 51, 96–110. https://doi.org/10.1111/etho.12377

- Imeri, S. & Rizzolli, M. (2022). CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance. o-bib. Das offene Bibliotheksjournal, 9 (2), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.5282/o-bib/5815

- Dukes, D., Abrams, K., Adolphs, R. et al. (2021). The rise of affectivism. Nature Human Behaviour 5, 816–820. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01130-8

Example 2: Conversation between Social and Cultural Anthropologists Anita von Poser and Birgitt Röttger-Rössler on Publishing Photos with Recognizable Individuals in Ethnological Research Contexts

As audio file, only in German

Source: Discussion on the Publication of Photos with B. Röttger-Rössler and Anita von Poser, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

As transcript

Birgitt Röttger-Rössler:

The law on copyright for works of visual art and photography states that photos may only be published with the consent of the depicted individuals. What many don’t know is that this is a very old law, originally enacted in 1907. Nevertheless, in our field, photos of people from various regions of the world have been published for decades without explicit, documented consent for such publication. Publishers didn’t insist on this either. Nowadays, however, this law is taken very seriously, partly due to digitization and the resulting uncontrollable spread and circulation of images. Of course, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), introduced in 2016, has also increased awareness regarding personal rights. In social and cultural anthropology, an attitude has now been established that rejects the publication of images where individuals are recognizable, even if it’s legally permissible, such as in images where people only appear incidentally in a landscape or other settings.

Today, I’m discussing this topic with Anita von Poser. Anita von Poser is a professor of social and cultural anthropology at Martin Luther University in Halle. She has conducted long-term, classic field research in Papua New Guinea in a village along the Ramu River and, more recently, field research in the transnational setting of Vietnamese Berlin.

Anita, publishing portrait photos of research participants has almost become taboo in our field. However, in your 2016 monograph "Foodways and Empathy," you published several photos of people, mentioning their real names. What’s behind this decision?

Anita von Poser:

Yes, Birgitt, thank you for your question. Perhaps just a bit of context: as you know, I conducted my research between 2004 and 2010. The book was first published in 2013, followed by a paperback edition in 2016. At that time, the discussions and legal regulations you’ve just mentioned were not as widely discussed as they are now.

Nevertheless, for ethical research reasons, I already gave a lot of thought to which photos I could and should include in "Foodways and Empathy," and I discussed this early on with my research partners in the field in Papua New Guinea. The response was always very clear: of course, it was important for the readers to know exactly who took care of me, who ensured my well-being, and who helped make the research possible.

I was also expected to signal my place within the local social structure. Omitting images of these important individuals and fundamental social relationships would have been seen as a sign of disrespect. Mentioning people by their real names was clearly meant as a sign of appreciation, considered socio-culturally acceptable from the specific local perspectives at the time of my research.

I believe that current discussions should allow more space for diverse opinions and attitudes on this topic, which can vary depending on where and with whom we conduct research. And, of course, we anthropologists must take these seriously.

Regarding my images: I was careful to anonymize specific social details and events, which I also discussed with my research partners. The images I selected beyond simple portraits depict scenes of public and ritualized behavior. While I did participate in intimate and private events during my long-term fieldwork, I consciously chose not to document such moments. These decisions were always made together with my research partners.

Birgitt Röttger-Rössler:

Thank you for these insights, Anita. These are indeed ethical considerations, highlighting the recognition and visibility of your research partners, their families, and the individuals who welcomed, supported, and accompanied you. Did the publisher at the time require you to prove that you had obtained consent for these images, or was that not necessary?

Anita von Poser:

Here, I can give a straightforward answer: No, the publisher only asked me to confirm that if I used photos taken by someone else, I would acknowledge this accordingly – which I did. I believe there are two such images in my book. One was taken by a research partner, and the other by my partner, who is also an anthropologist and visited me in the field.

At that time, the publisher didn’t inquire whether the individuals depicted had given their consent. As I’ve just explained, for me – and I believe also for our field of social and cultural anthropology when we teach and explain our methodological approaches – it’s fundamentally a research-ethical matter to make decisions about photos collaboratively with our field partners.

Birgitt Röttger-Rössler:

Nowadays, this is becoming more formalized. Publishers now typically require explicit consent due to GDPR regulations, which are not always easy to obtain. Some colleagues have started to record verbal consent using audio recordings since sending or completing consent forms can be challenging.

I believe this is linked to the fact that many of our works are now available through open-source platforms, circulating widely, leaving us with little control over how images are used. This is different from the past, when books had to be borrowed, purchased, or accessed in libraries – and copying images was more cumbersome, which provided a degree of protection.

I’d like to add one final comment. Due to the understandable and necessary heightened sensitivity around these issues, I’ve observed increasing uncertainty in our field regarding the publication of photographs showing people, even when they have given consent. I have mixed feelings about this. Photos convey so much – they speak to us and create connections. This is especially true for images of people, particularly portraits.

Pixelated faces, in a way, dehumanize individuals. Do we now have to completely abandon using photographs of people in our publications because of the uncontrollable ways images are shared today?

Anita von Poser:

I completely agree with you – images hold powerful meaning. They convey something in a way that words sometimes cannot capture. Digitization has indeed led to the uncontrollability you’ve described, and that’s unfortunate. But whether we should forgo the impactful nature of images and what they can communicate – I think that’s a process we must continue to discuss with our research partners.

It’s not a decision we as researchers can make alone. I believe this must be discussed collectively with the individuals, groups, communities, and societies we engage with in our work. It’s undoubtedly a delicate process, but one that should lead to further dialogue.

Birgitt Röttger-Rössler:

Thank you, Anita! I think your final words are very important – this is a process that is far from over. Thank you very much for this conversation.

Anita von Poser:

Thank you as well, dear Birgitt.

Tools

- CC License Chooser: To create the appropriate CC license with standardized license texts: https://creativecommons.org/chooser/

- General FAQs on CC Licenses: https://creativecommons.org/faq/

- FAQs on Using CC-Licensed Materials in Your Own Work: https://creativecommons.org/faq/#combining-and-adapting-cc-material

- License Notice Generator: Generates proper license notices for images from Wikipedia/Wikimedia Commons for reuse: https://lizenzhinweisgenerator.de/?lang=en

- Overview of Various International Licenses: https://www.dcc.ac.uk/guidance/how-guides/license-research-data#x1-4000

Notes

- 1See the list of relevant legal areas in research data management from Humboldt University of Berlin: https://www.cms.hu-berlin.de/de/dl/dataman/teilen/rechtliche-aspekte/rechtliche-aspekte

- 2Translated by Saskia Köbschall.

- 3See the

legal text here: https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/kunsturhg/__22.html - 4According to the license, attribution of the authors is not mandatory for this image; however, it is advisable to cite the source to ensure legal security and to honor the authors.

Literature and References

Brettschneider, P., Axtmann, A., Böker, E. & von Suchodoletz, D. (2021). Offene Lizenzen für Forschungsdaten: Rechtliche Bewertung und Praxistauglichkeit verbreiteter Lizenzmodelle. O-Bib. Das Offene Bibliotheksjournal. Herausgeber VDB, 8 (3), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.5282/o-bib/5749

Creative Commons. (2023a). Share your work. Creative Commons. https://creativecommons.org/share-your-work/

Creative Commons. (2023c). Combining and adapting CC Material. Creative Commons. https://creativecommons.org/faq/#combining-and-adapting-cc-material

Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG). (2014). Appell zur Nutzung offener Lizenzen in der Wissenschaft. Information für die Wissenschaft Nr. 6. https://www.dfg.de/de/aktuelles/neuigkeiten-themen/info-wissenschaft/2014/info-wissenschaft-14-68

Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft. (DFG, 2022). Leitlinien zur Sicherung guter wissenschaftlicher Praxis. Kodex. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6472827

Forschungsdaten.info. (2023j). Rechte und Forschungsdaten – Ein Überblick. forschungsdaten.info. https://forschungsdaten.info/themen/rechte-und-pflichten/recht-und-forschungsdaten-ein-ueberblick/

Gesetz betreffend das Urheberrecht an Werken der bildenden Künste und der Photographie. (KunstUrhG, 2001). Kunsturheberrechtsgesetz. https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/kunsturhg/

Gesetz über Urheberrecht und verwandte Schutzrechte. (UrhG, 2021). Urheberrechtsgesetz. https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/urhg/

Klimpel, P. (2019): Bearbeitungen frei lizenzierter Inhalte richtig kennzeichnen. iRight.info

https://irights.info/artikel/bearbeitungen-frei-lizenzierter-inhalte-richtig-kennzeichnen/29555Klimpel, P. (2020): Kulturelles Erbe digital. Eine kleine Rechtsfibel. digiS, Berlin. https://doi.org/10.12752/2.0.004.0

Kreutzer, T., & Lahmann, H. (2021). Rechtsfragen bei Open Science: Ein Leitfaden. Hamburg University Press. https://doi.org/10.15460/HUP.211

Lauber-Rönsberg, A., Krahn, P., Baumann, P. (2018). Gutachten zu den rechtlichen Rahmenbedingungen des Forschungsdatenmanagements im Rahmen des DataJus-Projektes. https://tu-dresden.de/gsw/jura/igewem/jfbimd13/ressourcen/dateien/publikationen/DataJus_Zusammenfassung_Gutachten_12-07-18.pdf

Universitätsbibliothek Technische Universität München (TUM) (2023). Handreichung zu rechtlichen Aspekten des Forschungsdatenmanagements. https://mediatum.ub.tum.de/doc/1690463/document.pdf

Wünsche, S., Soßna, V., Kreitlow, V. & Voigt, P. (2022). Urheberrechte an Forschungsdaten – Typische Unsicherheiten und wie man sie vermindern könnte. Ein Diskussionsimpuls. Bausteine Forschungsdatenmanagement. Empfehlungen und Erfahrungsberichte für die Praxis von Forschungsdatenmanagerinnen und -managern, Nr. 1/2022 (26-42). https://doi.org/10.17192/bfdm.2022.1.8369

Citation

Voigt, A. (2023). Rights and Licenses. In Data Affairs. Data Management in Ethnographic Research. SFB 1171 and Center for Digital Systems, Freie Universität Berlin. https://en.data-affairs.affective-societies.de/article/rights-and-licenses/