Recording Formats and Strategies

Definition

The term "recording" is used here in a broad sense: it encompasses both the open format of field notes, in which field researchers document what they have observed, heard, inquired about, and experienced, as well as the elaboration of these notes into complex protocols. It also includes the entry of specific information (e.g., census surveysThe term census (from Latin census) refers to population censuses, i.e., comprehensive surveys of a country's population. Over 2,000 years ago, similar censuses were conducted every five years in the Roman Empire to gather information about population structure and wealth distribution. In 2022, Germany conducted a register-based census (i.e., relying on official registry data), supplemented by a sample survey and a building and housing survey. Read More, time allocation studiesA time allocation study systematically measures the amount of time individuals spend on specific tasks and activities. These studies examine how people budget their time in various social and cultural contexts. For example, they explore how the division of labor in productive and reproductive activities is organized across genders and generations: How much time per day do mothers, fathers, older siblings, grandparents, and others spend caring for young children? How much time is allocated by whom to economic activities, caregiving tasks, or neighborhood interactions? Various methods are used to measure time budgeting, generating quantitative and replicable datasets. Read More) into pre-structured data collection forms.

Introduction

“Anthropologists are those who write things down at the end of the day”.

(Jackson, 1990, p. 15)

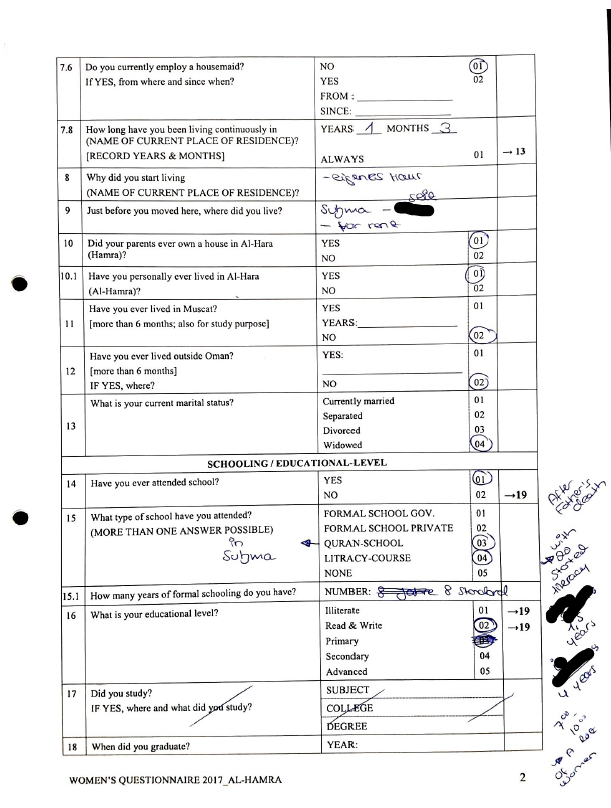

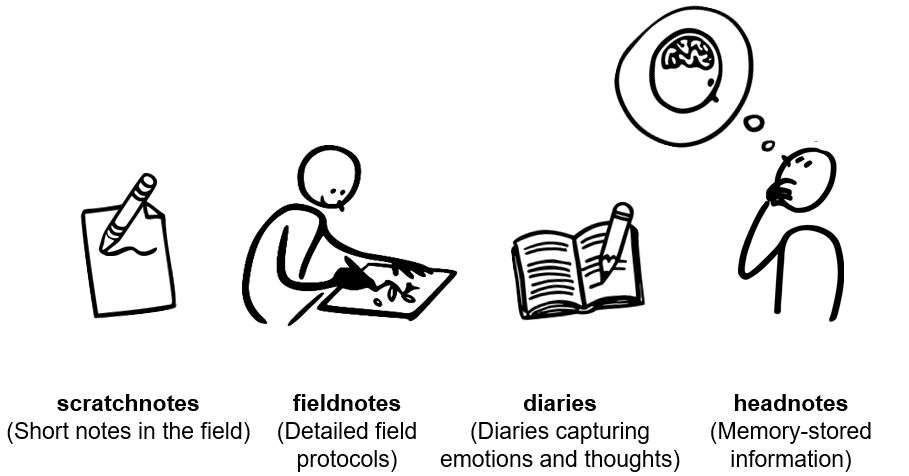

This section addresses a central aspect of social and cultural anthropological recording strategies: the creation of field notes and their subsequent daily elaboration, typically in the evenings, into detailed descriptions of the day’s observations, experiences, and inquiries. Short, keyword-based notes, often handwritten in notebooks and serving as memory aids for ethnographers, are typically expanded into extensive research protocols spanning numerous pages. In English-language literature, these research protocols derived from brief notes (scratchnotes, jottings) are commonly referred to as “fieldnotes” (Sanjek, 1990, pp. 97). Fieldnotes are chronological, which facilitates reconstructing the research process during analysis. Ideally written daily, they typically contain diverse information about social life, which is later synthesized into meaningful units during analysis. In this sense, they can be seen as the "pretext for ethnography" (Lederman, 1990).

Many researchers also keep personal diaries, documenting their experiences and emotions. However, many report difficulty in separating these formats, leading to intertwined entries. As a result, personal emotions and perceptions are often embedded in research protocols, while ethnographic descriptions find their way into diaries. Importantly, social and cultural anthropologists produce these three core textual formats – scratchnotes, fieldnotes, and diaries – primarily for themselves, meaning they are decipherable only by the authors (Lederman, 1990, p. 72). This self-referential nature raises concerns among ethnographers about how open-science demands may significantly alter their recording routines by introducing potential secondary users as an imagined readership, thereby profoundly changing the nature of fieldnotes (see also the article Data in Ethnographic Research).

In addition to these three textual formats, “headnotes” – information stored in memory – also play a significant role. These implicit, unrecorded insights, accumulated during research, are invaluable for interpreting research documents and materials:

„We come back from the field with fieldnotes and headnotes. The fieldnotes stay the same, written down on paper, but the headnotes continue to evolve and change as they did during the time in the field.”

(Sanjek, 1990, p. 93)

This underscores the importance of memory-stored information, which, despite not being recorded, plays a critical role during analysis and the writing of ethnographic texts (see also Fabian, 2011). Scratchnotes and headnotes are particularly vital in situations where no formal recording – on paper or digitally – is possible, requiring researchers to rely entirely on their memory for later documentation.

Source: Text formats in ethnographic research, Anne Voigt with CoCoMaterial, 2023, lizenziert unter CC BY-SA 4.0

As an example, reference can be made to the research conducted by Meike Meerpohl on Trans-Saharan trade in Chad between 2003 and 2007, which was affected by the violent Darfur conflict and thus marked by numerous politically sensitive situations during which immediate note-taking was impossible, necessitating that much of the data had to be recorded retrospectively from memory. Meerpohl reports frequently encountering deep-seated mistrust, which made open note-taking during conversations, the use of recording devices, and the open mapping of local market structures impossible, so that much had to be documented afterwards (Meerpohl, 2009, p. 32). She attributes the skepticism toward foreigners prevalent in Chad to the prolonged civil war, the French colonial rule, and a repressive state (Meerpohl, 2009, p. 35). Similarly, during her participation in a 1,000 km desert crossing with a camel caravan, the researcher was unable to maintain regular daily notes or conduct extensive interviews, as she was simply too exhausted in the evenings after 12 to 15 hours of camel riding (Meerpohl, 2009).

Even in less challenging field contexts, the insights gained through participant observation can only be recorded retrospectively, although this is usually done without significant delay to minimize forgetting. The limits of documentation are particularly evident in the numerous multisensory impressions researchers gain during participant observation. These can only be partially verbalized and largely remain in the embodied memory of the researchers.

Motivation

The recording of information and findings is the central element of ethnographic work, which is why it is important to engage with this topic.

Methods

As a general rule, it is important to distinguish when preparing fieldnotes between what was observed (seen and heard) and what was asked. That is, which information the ethnographer gathered from a social situation without their own intervention by simply watching and listening, and which information was obtained by asking questions.

Furthermore, it is always necessary to record, in addition to the date and location, which individuals were involved in the respective event and how the ethnographer was positioned within the event. The latter is important to assess to what extent the situation was influenced by their own behavior. Guidance on creating fieldnotes can be found in most methodological handbooks (e.g., deWalt & deWalt, 2011; Beer & König, 2020).

In the past, social and cultural anthropologists primarily recorded their notes using pen, paper, and, at most, mechanical typewriters. Today, they have access to entirely different technical possibilities, including lightweight, portable laptops (which can also be powered by solar energy), smartphones, digital pens with recording functions, voice recognition software, mapping programs, and more. For instance, scratchnotes can be captured using a digital pen, daily logs can be directly typed (or spoken) into a computer, and – provided there are suitable network connections – secured in a cloud. However, it should be noted that files stored in a cloud are not entirely secure from external access (see articles on Data Storage and Data Security). Every activity on the internet leaves a trace, which is why it is strongly advised against storing field notes in clouds, even those provided by one’s own university. Instead, external hard drives and USB sticks should be used.

Depending on circumstances, a laptop may not always be the ideal tool – due to weather conditions, for example, or because such a device might attract undue attention. (There are numerous accounts of laptops becoming filled with sand, overheating in the sun, becoming too damp during rainy seasons, or being stolen.) In such cases, pen and paper or a classic travel typewriter may be more suitable.

It is also not advisable to rely exclusively on verbal recordings for field notes, such as speaking into a recording device and saving the result as an audio file. This approach omits an important step of reflection: the significantly more time-intensive process of typing or handwriting notes facilitates deeper cognitive engagement,pausing, sorting, and searching for appropriate formulations. This ensures that the recorded information is better retained in memory, while also revealing ambiguities, which can be crucial for further fieldwork. According to neuroscientific studies, handwriting is superior to typing in this regard, due to the spatial dimension of writing on paper (e.g., Mueller & Oppenheimer, 2014).

Systematic and Standardized Data Collection

These daily research protocols or fieldnotes are just one element of the recording formats that ethnographers use, depending on the methods they apply. However, it is important to understand that they are an absolute necessity and form the core of ethnographic work, even though other recording formats are also employed, not all of which are written. For example, written fieldnotes also play a central role in videographic research projects (e.g., Wetzels, 2021) or PhotoVoice studies (e.g., Röttger-Rössler & Seise, 2023; Röttger-Rössler et al., 2019), as they provide important information about the social context, specific events, and the researcher’s position. We can only briefly point to the methodological challenges associated with audio-visual survey methods here (e.g., Tuma et al., 2013). Special research situations also include online ethnographies, which are addressed separately in the article Online Ethnography.

Within the framework of classic participant observation, social and cultural anthropologists employ numerous other methods depending on the research question, many of which are quantitative in nature, such as demographic surveys, household surveysA household survey is an overview study conducted through standardized surveys of a representative sample or random sample of households within a study region (see: Survey/Survey Data). In social and cultural anthropology, the terms survey, household survey, and census are often used interchangeably. Read More, linguistic surveys, measurements of field sizes and harvest yields, or systematic observations like time allocation studiesA time allocation study systematically measures the amount of time individuals spend on specific tasks and activities. These studies examine how people budget their time in various social and cultural contexts. For example, they explore how the division of labor in productive and reproductive activities is organized across genders and generations: How much time per day do mothers, fathers, older siblings, grandparents, and others spend caring for young children? How much time is allocated by whom to economic activities, caregiving tasks, or neighborhood interactions? Various methods are used to measure time budgeting, generating quantitative and replicable datasets. Read More. Each of these specific methods involves particular modes of documentation, which must always be sensitively adapted to the respective cultural context and research conditions.

Practical Examples

The following examples from ethnographic practice provide insights into various methodological approaches, associated recording formats, and general challenges.

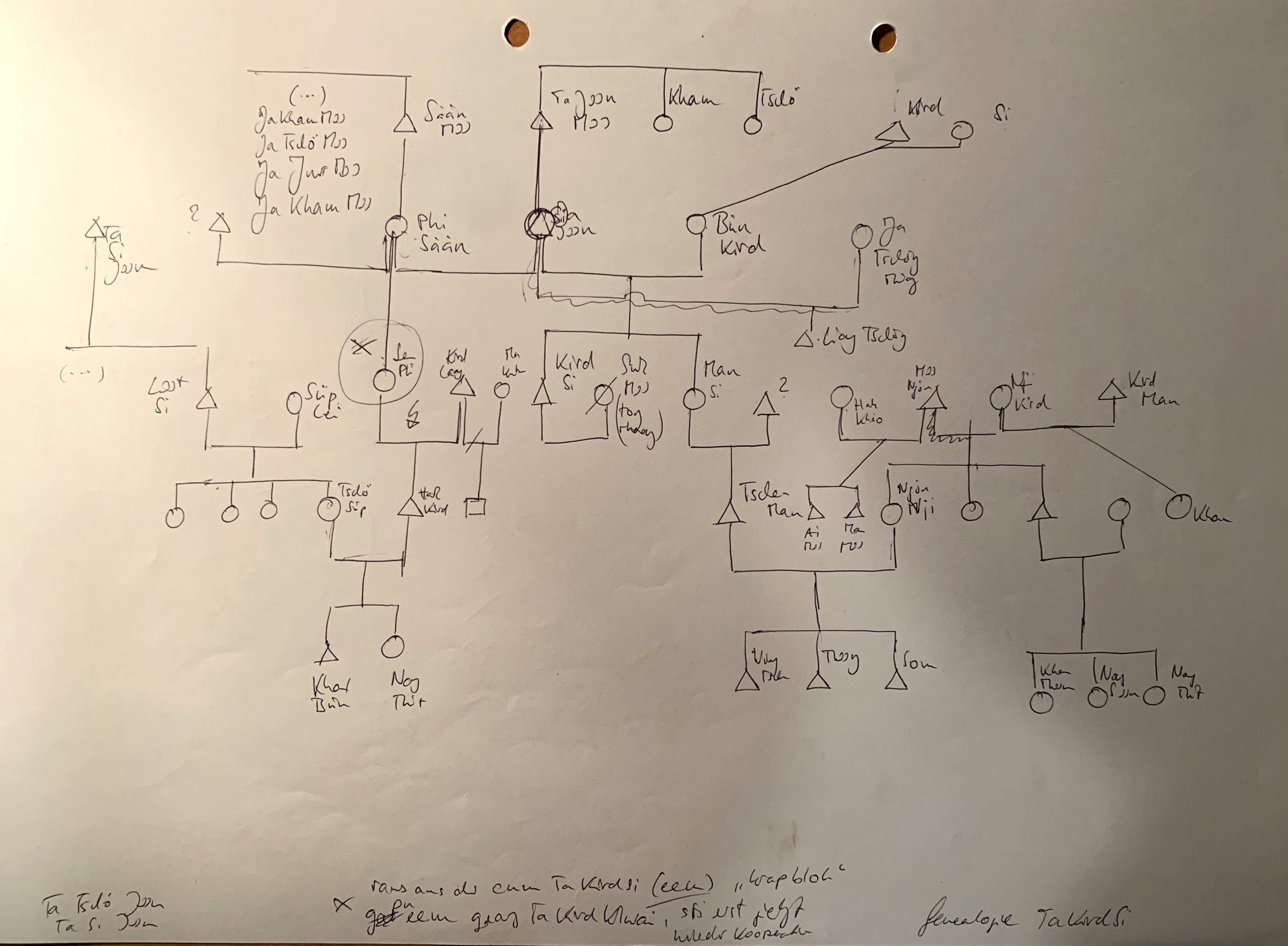

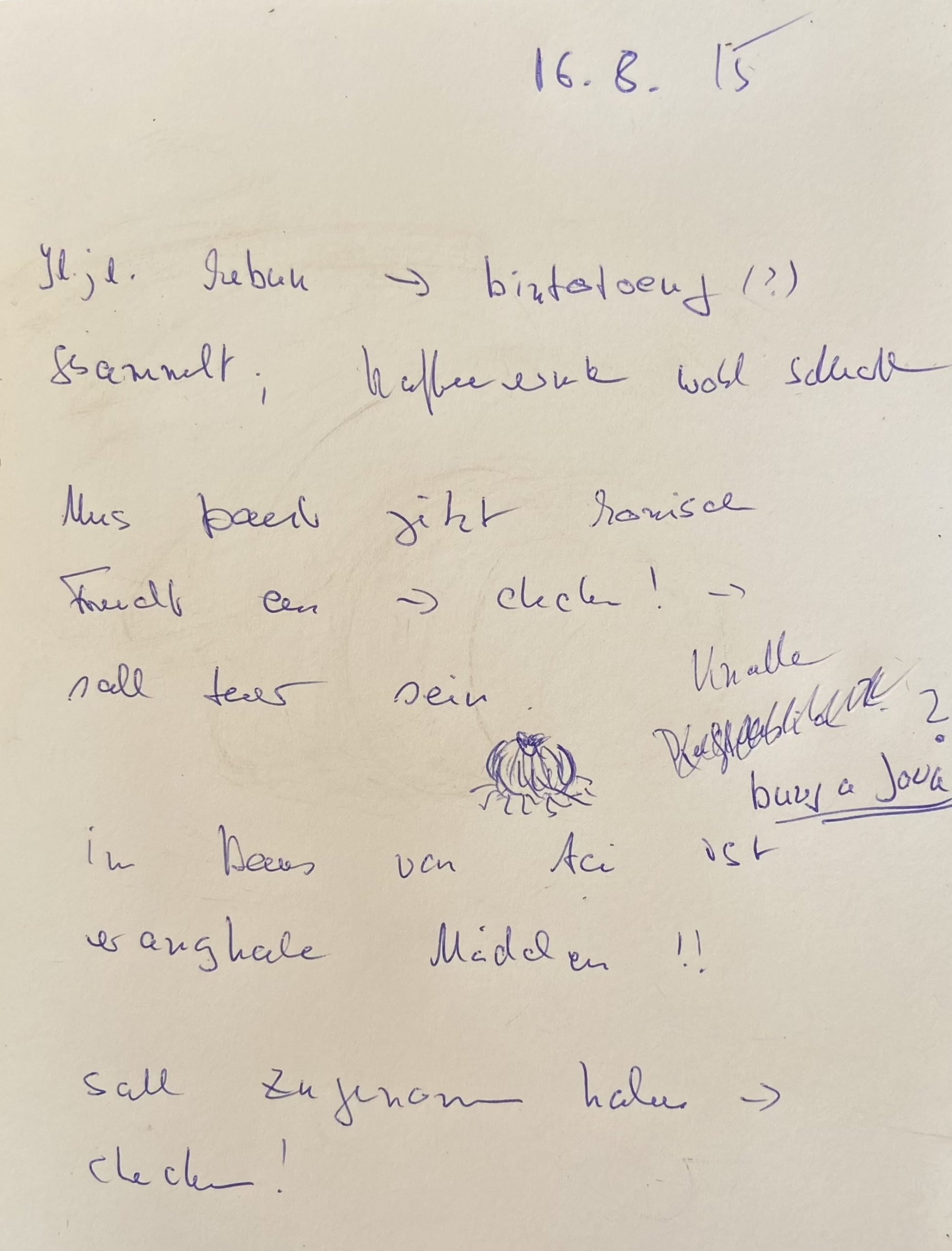

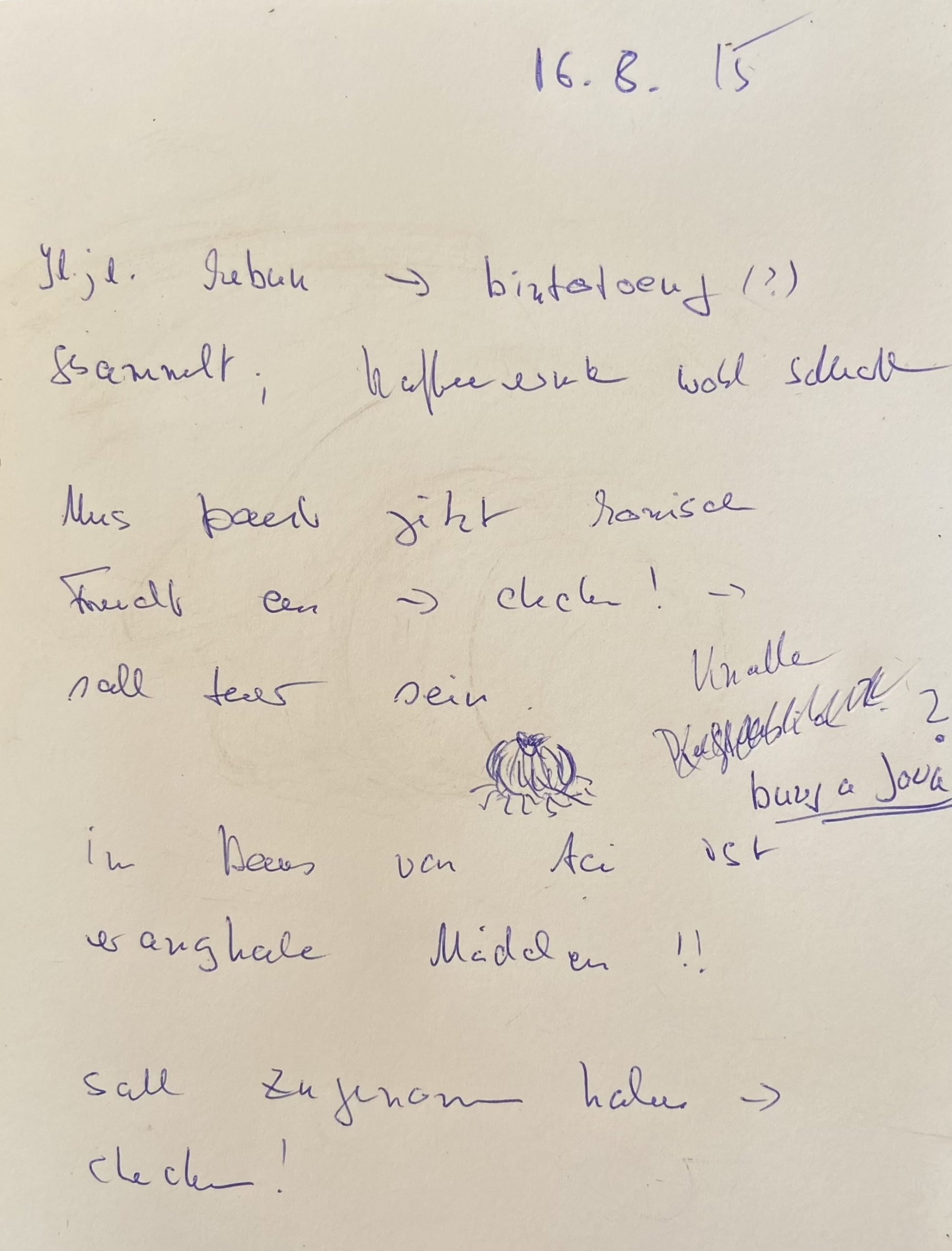

Example 1: Handwritten Notes as Fieldnotes (Birgitt Röttger-Rössler, 2015, and Rosalie Stolz, 2014)

Handwritten notes continue to be a central documentation technique for ethnographers. Notebooks are easy to carry, allow for quick note-taking and sketches, are independent of electricity, and represent an overall transparent recording medium. However, the protocols derived from these notes are nowadays typically typed directly into a laptop rather than being elaborated upon in handwritten form.

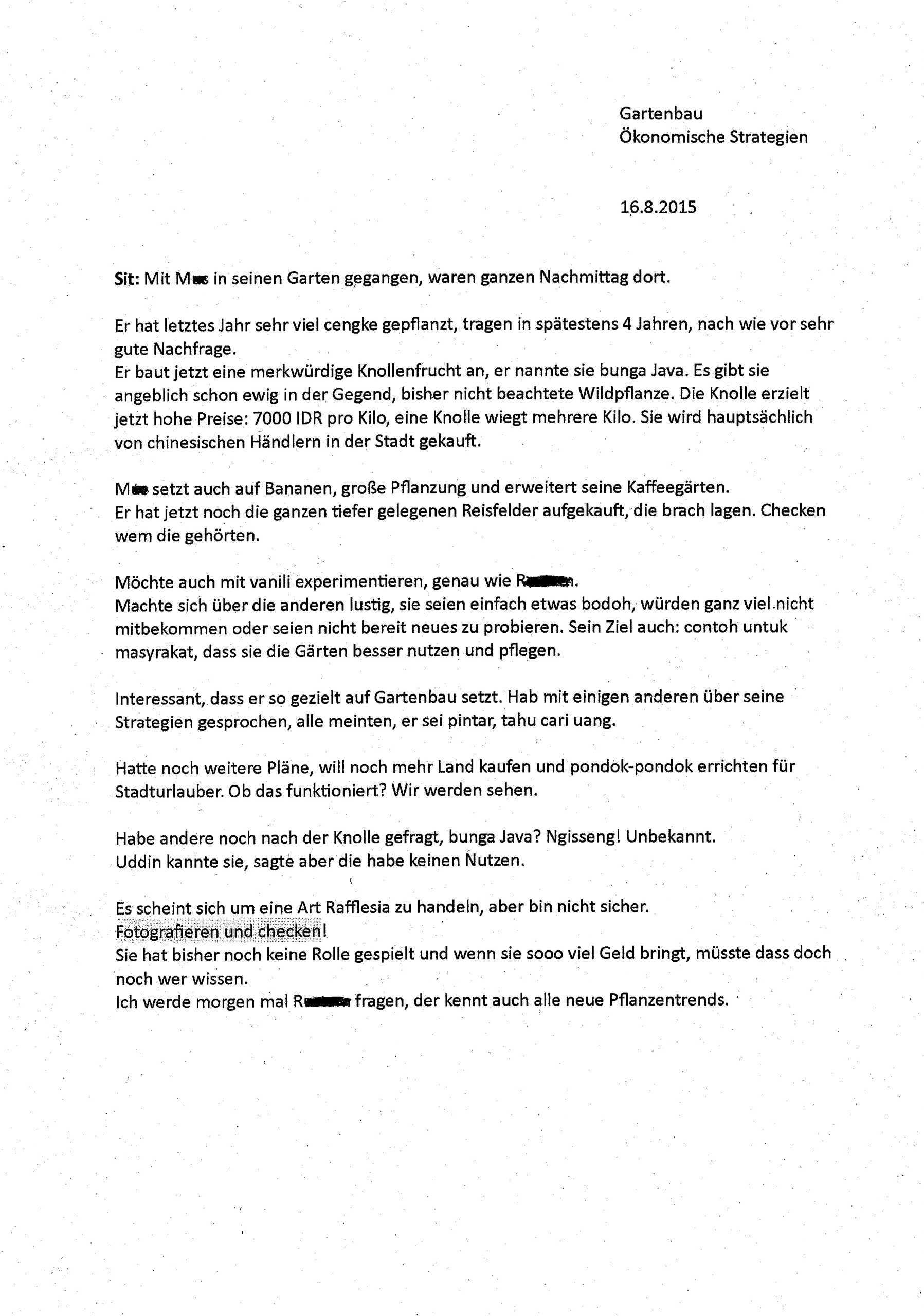

Horticulture, Economic Strategies, 16.8.2015

Sit: Went with M to his garden, spent the whole afternoon there.

He planted a lot of cengke last year, which will yield in no more than four years; still a very high demand.

He is now cultivating a peculiar tuber crop he called bunga Java. It is supposedly native to the area, a previously overlooked wild plant. The tuber now fetches high prices: 7000 IDR per kilo, with one tuber weighing several kilos. It is primarily purchased by Chinese traders in the city.

M is also focusing on bananas, has a large plantation, and is expanding his coffee gardens.

He has now also bought all the lower-lying rice fields that were lying fallow. Need to check who owned them.

He also wants to experiment with vanili, just like R.

M mocked others, saying they are simply a bit bodoh and either miss out on many things or are unwilling to try new ideas. His goal is also: contoh untuk masyarakat, so that they better use and care for their gardens.

Interesting that he is so deliberately focusing on horticulture. I talked to a few others about his strategies; they all said he is pintar, tahu cari uang.

He had additional plans, wants to buy even more land and build pondok-pondok for city vacationers. Will that work? We’ll see.

Asked others about the tuber, bunga Java? Ngisseng! Unknown. U… they knew, but said it had no use.

It seems to be a type of Rafflesia, but I’m not sure.

Take photos and check!

It has not played any role so far, and if it brings in sooo much money, surely someone else must know about it.

I’ll ask R tomorrow; he also knows all the new plant trends.

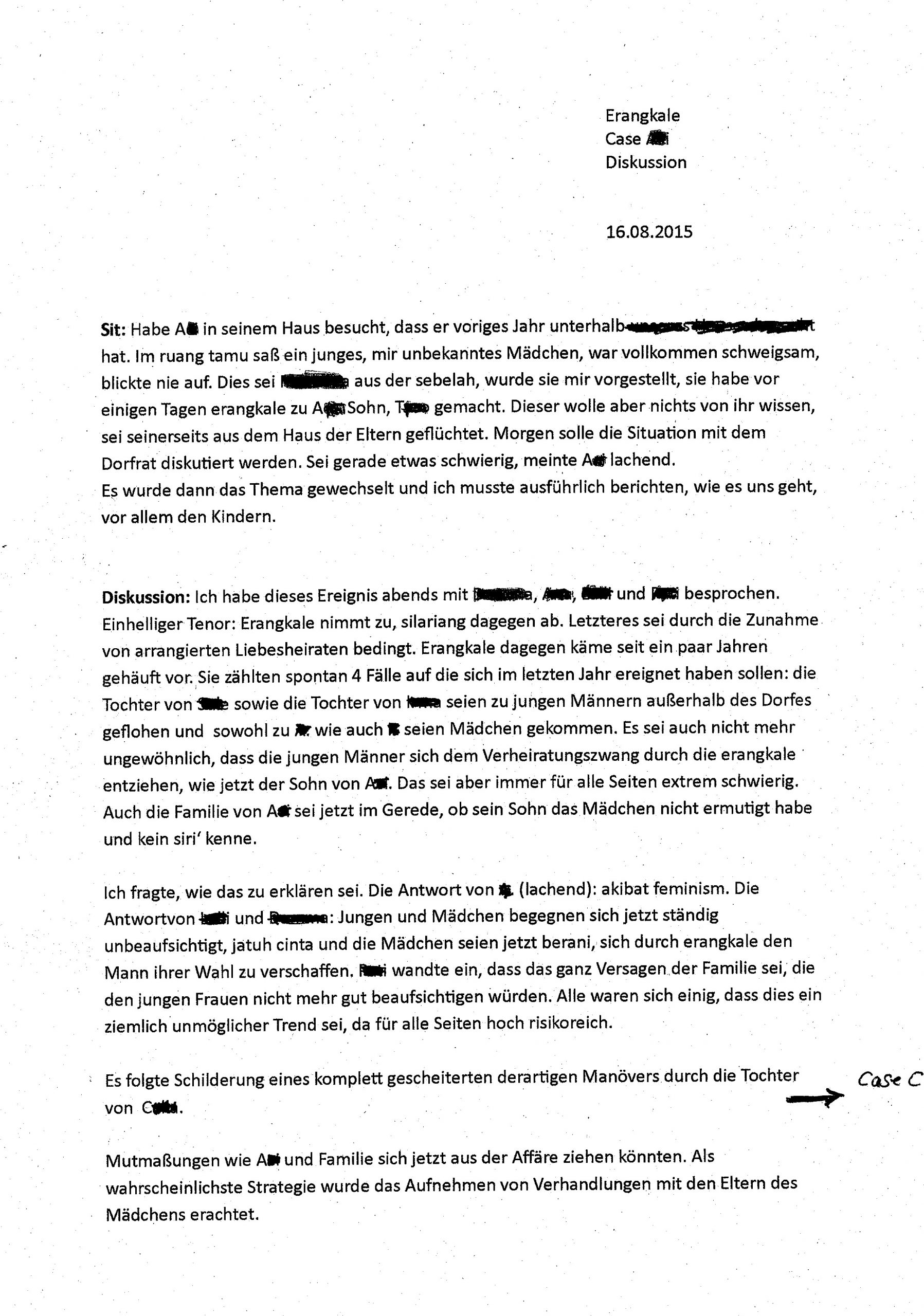

Erangkale, Case, Discussion, 16.08.2015

Sit: Visited A at his house, which he built last year below…. In the ruang tamu sat a young girl I didn’t know. She was completely silent, never looking up. This was…from the sebelah, she was introduced to me, she had recently done erangkale to A’s son, T. However, T didn’t want anything to do with her and had fled from his parents' house. The situation is supposed to be discussed with the village council tomorrow. Things are a bit complicated at the moment, A said, laughing. The topic was then changed, and I was asked to give a detailed account of how we are doing, especially the children.

Discussion: In the evening, I discussed this event with …, …, …, and …. The unanimous conclusion: Erangkale is increasing, while silariang is decreasing. The latter is attributed to the rise in arranged love marriages. On the other hand, erangkale has been occurring more frequently over the past few years. They spontaneously recounted four cases they said had happened in the past year: the daughter of … as well as the daughter of…fled to young men outside of the village and also to…as well as… his girls had come, It is also no longer unusual for young men to evade the marriage obligations imposed by erangkale, as A’s son has done now. However, this is always extremely difficult for all parties involved. Even A’s family is now the subject of gossip, whether his son might have encouraged the girl and does’t know siri´.

I asked how this could be explained. … The answer (laughing): akibat feminism. The answer from... and...: Boys and girls now constantly meet without supervision, jatuh cinta, and the girls met are now berani to use erangkale to secure the man of their choice. … objected, saying this was a complete failure of the family, who no longer properly supervise the young women. Everyone agreed that this was a rather unacceptable trend, as it is highly risky for all parties involved.

This was followed by a recounting of a completely failed maneuver of this kind by the daughter of …. Speculation arose about how A and his family might now extricate themselves from the situation. The most likely strategy was deemed to be initiating negotiations with the girl’s parents.

Example 2: Interview with Anthropologist Kathrin Bauer on Her Recording Strategies During Fieldwork in Colombia (2023)

Kathrin Bauer is conducting doctoral research on the topic "Diversity or Dysfunction. Bio-social-cultural Influences on Life with ADHD (traits) in Two Colombian Communities" under the supervision of Prof. Dr. Birgitt Röttger-Rössler at Freie Universität Berlin.

In the interview, she describes various recording formats and explains which ones she chose for different field contexts and why. She illustrates challenges and difficulties with specific situations and experiences from her fieldwork.

As audio file, only in German

Source: Interview on recording strategies in the field with C. Heldt and K. Bauer, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

As transcript

Camilla Heldt: Kathrin Bauer is sitting next to me. Hello, you are an anthropologist and currently analyzing the data from your doctoral research. You told me you returned from the field a year ago. What was the topic of your research, and where were you?

Kathrin Bauer: I conducted research on ADHD, that is, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, in Colombia. I did my initial fieldwork in Medellín, in an urban context, before the pandemic. Then, a year ago, I returned to the field for six months to conduct research in rural communities.

Camilla Heldt: And what recording strategies did you use in the field? For example, how did you record interviews?

Kathrin Bauer: For most interviews, I made audio recordings. Only in three cases did I rely on conversation notes. In the first two cases, it was because I was a bit shy and thought perhaps my conversation partners might feel uneasy if I recorded the interview. These were also somewhat sensitive topics. Only during the third interview did I ask if I could record it, and I then realized that for the participants, it was completely expected that an interview would be recorded. In fact, if I hadn’t recorded it, it might have even seemed less professional.

There was only one interviewee who preferred not to be recorded. For the rest, I used audio recording. Initially, I used my smartphone because I thought it had pretty good quality, and I didn’t have much money before going to the field for the first time. Plus, it’s a bit more discreet than a dedicated recording device.

At the start, I checked the recordings very thoroughly, but later on, only spot-checked them. Unfortunately, when I got back home, I discovered that there had been technical issues. These problems only appeared after the first minute of recording, meaning I ended up with a few lost audios. For these cases, I only had conversation notes, which weren’t very detailed since I had been relying on the audio recordings. That was quite frustrating.

It’s not a disaster for my research since I still have 130 hours of audio recordings, so it’s manageable. However, I do feel a bit guilty because I know how busy my interviewees were. Not being able to use these recordings as I intended still bothers me.

From then on, I started using a dedicated dictation device, while also recording simultaneously with my smartphone.

Camilla Heldt: Yes, thank you for sharing your experiences. So how did you record your field notes?

Kathrin Bauer: It was very important to me that I had them available digitally because I thought that would be an advantage during analysis. I also liked the almost unlimited storage space and the fact that I could travel with very light luggage. Plus, you don’t get the messy handwriting I sometimes end up with when I write a lot or very quickly by hand. I found it neater to correct or add to them afterward, and I liked the option of cloud storage. I know there are data protection concerns about that, but I still found it very practical because, on the one hand, I always had access to the data regardless of the recording device. On the other hand, I thought it was even less secure to have a physical notebook lying around that could get lost or stolen – you never know. And in that case, it would be much easier to associate the statements with individuals in their context than it would be with digital notes. So, I still felt that digital notes were safer than handwritten ones.

Camilla Heldt: I can understand that. How did you actually implement these digital notes?

Kathrin Bauer: At first, I used a laptop, but I had already started taking short notes on my smartphone – just quick points to ensure I wouldn’t forget anything before I could write my field notes. Over time, I gradually shifted to making most of my field notes on my smartphone and then supplementing them with a tablet and an external keyboard. That had several advantages for me. First, I’m quite fast with the swipe mode on the phone. And since you always have your phone with you, you can jot down quick notes anywhere – in the bathroom, on a train, or on a bus. Sometimes, you can even jot something down quickly during the actual situation. Another advantage is that it’s good to use in places with limited electricity access. I had a solar power bank, so I could always charge my phone, which would have been harder with a laptop. I also didn’t need a lamp or a table, so I could still write my field notes at night in the dark while lying in bed.

Camilla Heldt: You’ve outlined the benefits of digital tools very well. Did you also use good old paper at times?

Kathrin Bauer: Yes, I conducted a lot of observations in schools, for example during lessons, and naturally created observation logs. I preferred using a tablet for that because, compared to a smartphone, it doesn’t make you look distracted. Plus, if students aren’t allowed to use smartphones, it feels wrong for me to sit there using one. A tablet seemed better because it offered all the digital advantages. I found it more pleasant to write on, and it could convert handwritten notes into legible text. However, a tablet wasn’t ideal in a classroom because it was distracting for the students – they’d get curious, want to look at it, or even try to play with it. That made me nervous because it was one of my main tools in the field. So, I switched to using a notebook, which was much less conspicuous, and later transcribed those notes. That said, I did get caught in a couple of heavy rainstorms, and my notebook got pretty soaked – at least parts of it. So, it’s very important to use ink that doesn’t smear easily when it gets wet.

Camilla Heldt: Yes, you have to be careful about that. So, would you say, in conclusion, that a mix of analog and digital recording strategies is advisable?

Kathrin Bauer: I’d say you should keep everything in mind and have a kind of toolbox to flexibly choose the recording medium. If you’re researching in just one context, it makes sense to stick to the medium that works best there. But if, like me, you’re working in different contexts – urban and rural, schools, and other environments – then it makes sense to combine various recording methods.

Camilla Heldt: Thank you for your insights, and thanks for the conversation!

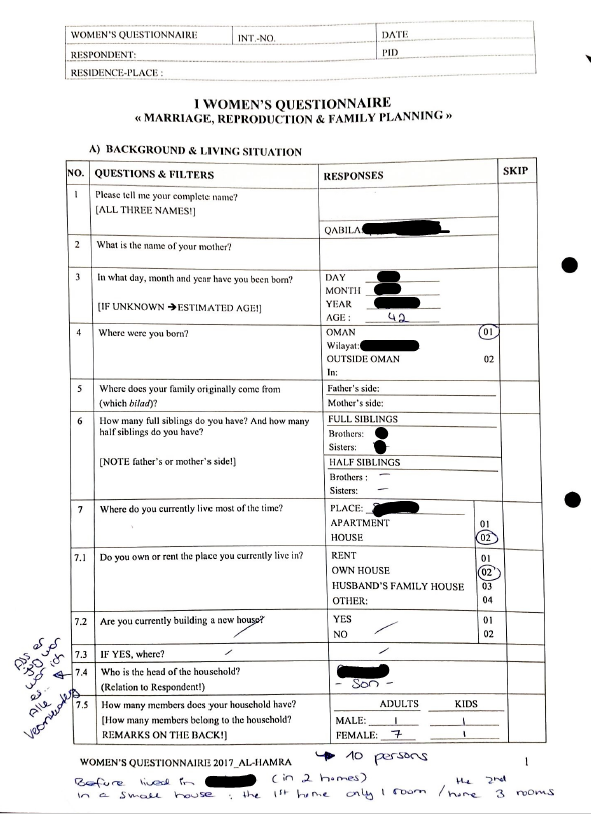

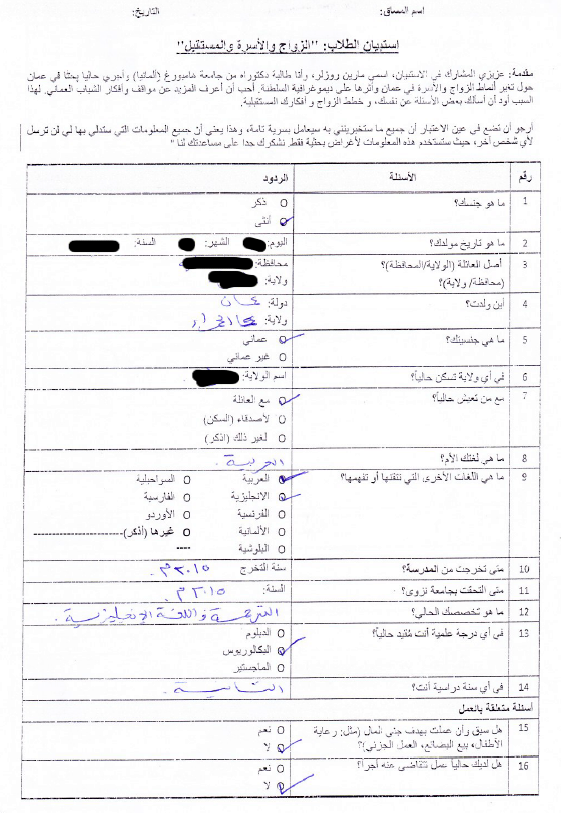

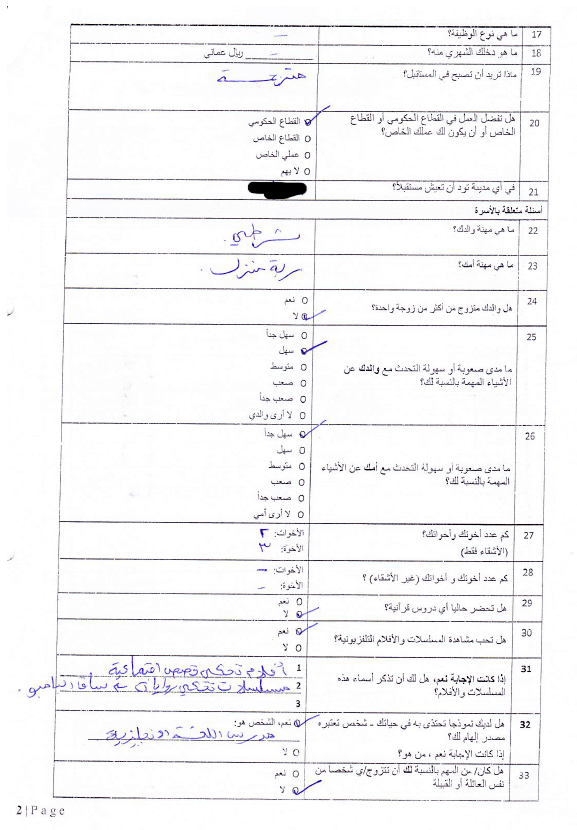

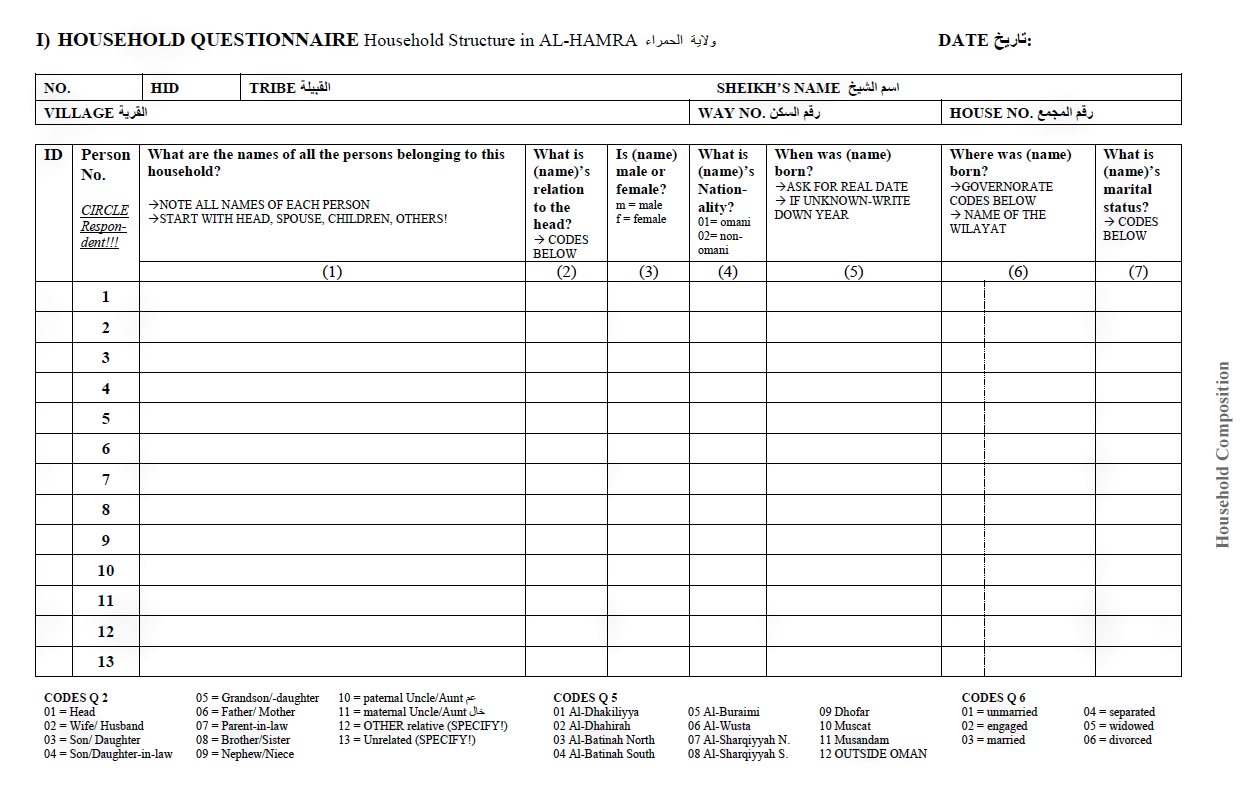

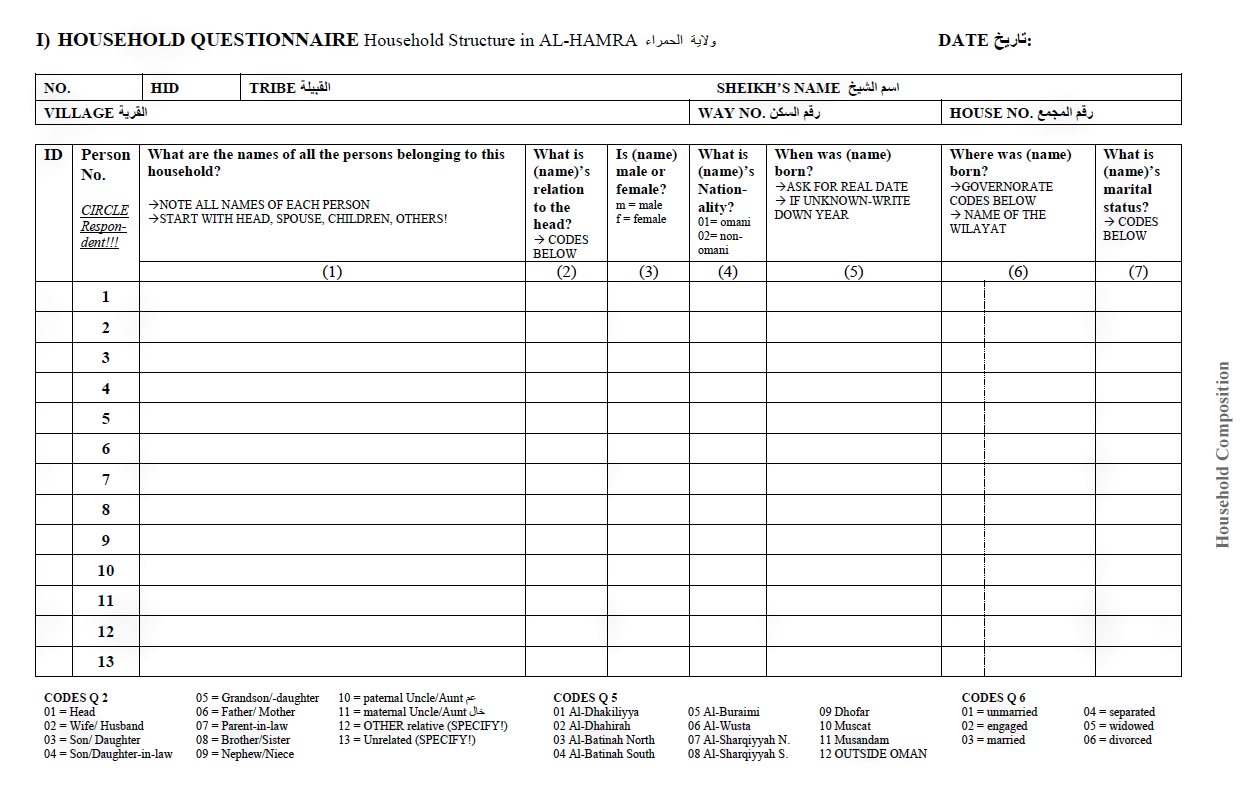

Example 3: Interview with Anthropologist Maren Jordan on Field Recording Strategies (2023) and Standardized Questionnaires (2016/17)

For her doctoral research, Maren Jordan conducted fieldwork between 2016 and 2017 on the topic of marriage, reproduction, and family planning in the small town of Al-Hamra in northern Oman. The research was part of the DFG-funded project "Fertile Transformation in the Sultanate of Oman: Ethnological Explanations of Demographic Dynamics" under the direction of Prof. Dr. Julia Pauli and Prof. Dr. Laila Prager at the University of Hamburg.

In the interview, Maren Jordan describes her methodological approach in the field and discusses the advantages and disadvantages of paper as a recording medium.

As audio file, only in German

Source: Interview on field recording strategies with C. Heldt and M. Jordan, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

As transcript

Camilla Heldt: I’m speaking today with anthropologist Maren Jordan. Nice to have you here! Tell us again, where did you conduct your doctoral research and what was your topic?

Maren Jordan: Thank you for having me. The topic of my research was the demographic change in Oman. As part of my doctoral project, I conducted a year of fieldwork between 2016 and 2017 in northern Oman. The goal was to investigate the fertility decline since the 1980s through an ethnodemographic case study. I aimed to find out why this decline occurred and what consequences it has had. I also explored how sociocultural norms, values, and practices surrounding pregnancy, childbirth, and family planning have changed.

Camilla Heldt: That sounds really fascinating! How did you approach this topic methodologically?

Maren Jordan: I used many different methods, following a so-called “mixed methods” approach. This included both classical ethnographic methods—such as qualitative interviews, participant observation, and group discussions—and quantitative methods. These diverse methods required very different recording strategies, including handwritten and digital notes as well as audio recordings. An important aspect of my research design was that the qualitative recordings and notes formed the basis for the standardized questionnaires I conducted at the end of my fieldwork.

Specifically, I created three different questionnaires: a classic demographic household survey, a questionnaire for collecting women’s birth histories across various age groups, and a questionnaire for university students.

Camilla Heldt: Oh yes, and you already told me that developing these questionnaires took several months while you were already in the field in Oman. Why was this such a time-consuming process?

Maren Jordan: Yes, exactly. There are several reasons for this: First, the field itself. We’re talking about a religiously conservative small town in rural Oman. Then, the research topic is very sensitive. Building trust was necessary to ask questions about marriage, contraception, and birth histories. Second, qualitative fieldwork was required to determine the right questions to ask and what was locally significant. I also had to learn the correct local Arabic terms. All of this takes time.

But this is also the value of ethnographic research. Unlike demographers who often work with pre-designed surveys that don’t include locally adapted questions, ethnographic research first identifies which categories are relevant. Asking the wrong questions generates inaccurate answers.

Camilla Heldt: I find that extremely interesting and also very understandable that designing the questionnaires took so much time. But once the questionnaires were ready, you printed them out and distributed them in paper form to participants for completion or used them during conversations. Why did you choose this fixed paper format?

Maren Jordan: Mainly for a practical reason: I didn’t have an iPad or digital data collection tools available. But I also saw many advantages in the paper format. Especially during interviews with women from older generations, the paper format created a sense of closeness. I wasn’t looking at a phone; I was writing on paper during the interview. I personally conducted all the interviews, and this approach was simply more respectful in that context. Another important aspect was that I could make notes in the margins, which would have been lost in a digital input form.

For the questionnaire survey with students, there was another consideration: I achieved a higher response rate. Data quality was a crucial criterion. I distributed the questionnaires in classrooms, but I was physically present in the room. I introduced myself in detail and could answer questions. This resulted in 470 completed questionnaires, which I then manually entered into SPSS, a statistical software, back in Germany after fieldwork ended.

And this is also a clear disadvantage of non-digital paper questionnaires: the considerable time required. On the other hand, you can make corrections retrospectively, and there’s an additional step of reflection.

All in all, I remain a fan of paper. It provides a tangible record: the field diaries, the binders filled with handwritten notes, sitting on the shelf. Even the paper still carries the scent of incense and bakhour from the field and the memories remain so tangible.

Camilla Heldt: That sounds really beautiful! Thank you for sharing insights into your research and illustrating the advantages and disadvantages of digital and analog recording strategies!

Maren Jordan: Thank you very much.

The researcher Maren Jordan utilized questionnaires in addition to qualitative methods during her research on marriage, reproduction, and family planning in Oman. She opted to use printed paper versions of the questionnaires during her interviews and distributed them in an analog format to students in seminar rooms. This approach not only allowed her to make relevant notes in the margins but also resulted in a high response rate for the distributed questionnaires. These were later transferred to Excel and analyzed using SPSS Statistics software.

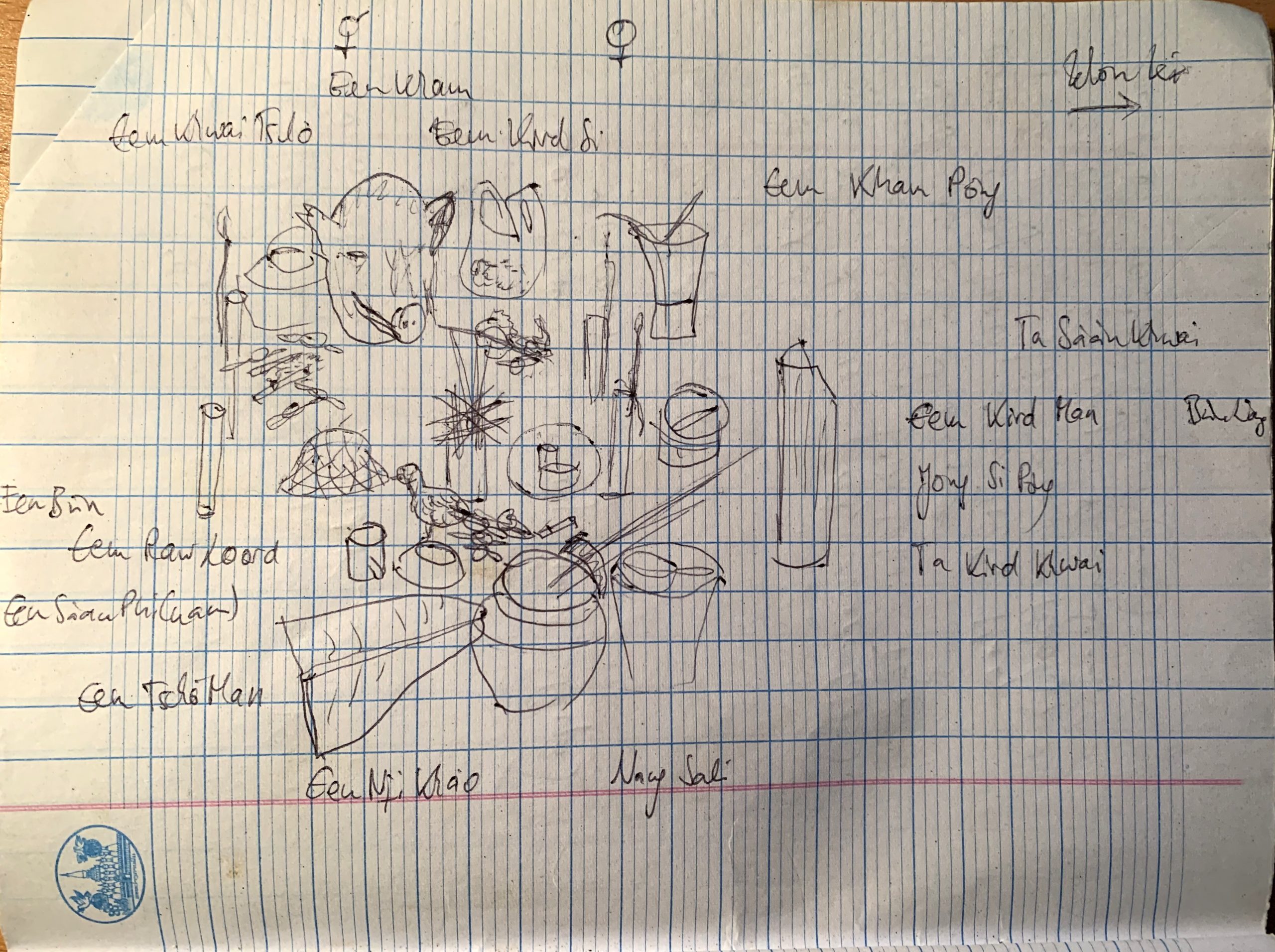

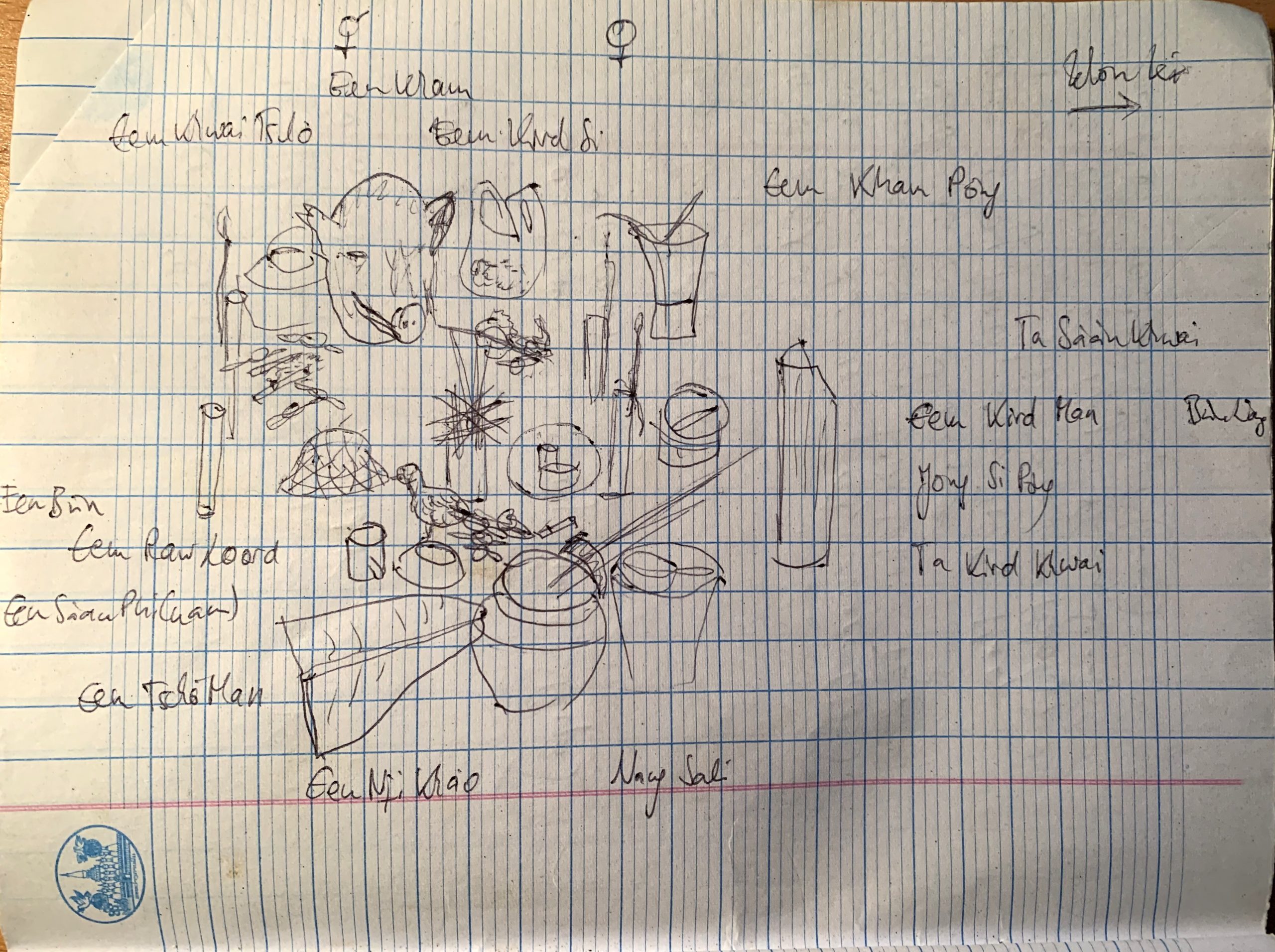

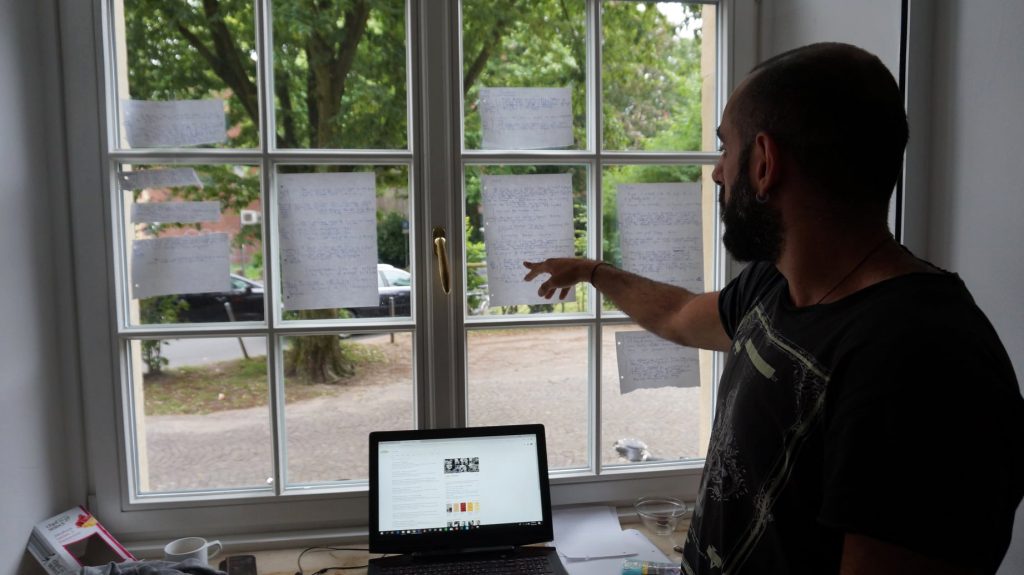

Example 4: Visual and Audiovisual Data Collection Techniques, Thomas John (2018)

Visual and audiovisual data collection techniques, such as video interviews or the cinematic documentation of rituals, work techniques, etc., also play a significant role.

The image illustrates the process of analyzing film material within a seminar on visual anthropology at the University of Münster. Key statements made by the interviewed protagonists are extracted from the film and "visualized" in written form to develop an analytical narrative.

Source: Film material analysis within a seminar on visual anthropology at the University of Münster, Thomas John, 2018, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Example 5: Multi-sensory Information During Participation in a Ritual, Dominik Mattes (2022)

The multi-sensory impressions experienced by researchers during participant observation can never be fully captured linguistically in protocols; they largely remain within the bodily memory of ethnographers. In this sense, the body can also be understood as a recording medium that plays an essential role in ethnographic research.

Dominik Mattes conducted research at SFB1171 in the project: Governing Religious Diversity in Berlin. Affective Dynamics of Inclusion and Exclusion in Urban Spaces. The image shows his participation in a public neo-pagan ritual centered on the transformative power of fire, held during Berlin's Long Night of Religions (2022). It illustrates the multi-sensory information that researchers gain through participant observation (Mattes et al., forthcoming).

Source: Participation of the researcher in a neo-pagan ritual during Berlin's Long Night of Religions, Thomas John, 2022, All rights reserved.

Literature and References

Beer, B. & König, A. (Eds.).( 2020). Methoden ethnologischer Feldforschung. Ethnologische Paperbacks. (3rd ed.). Dietrich Reimer Verlag.

DeWalt, K. M. & DeWalt, B. R. (2011). Participant Observation: A Guide for Fieldworkers. Lanham, Md: Rowman & Littlefield.

Fabian, J. (2011). Ethnography and Memory. In Melhuus, M., Jon P. Mitchell, J. P. & Wulff, H. (Eds.) (2011). Ethnographic Practice in the Present. New York. Berghahn.

Jackson, J. E. (1990). ‘‘I Am a Fieldnote’’: Fieldnotes as a Symbol of Professional Identity. Sanjek, R. (Ed.). (1990). Fieldnotes: The Makings of Anthropology. Cornell University Press. https://doi.org/10.7591/9781501711954-002

Lederman, R. (1990). Pretexts for Ethnography: On Reading Fieldnotes. In Sanjek, R. (Eds.). (1990). Fieldnotes: The Makings of Anthropology. Ithaca. Cornell University Press.

Meerpohl, M. (2009). Kamele und Zucker. Transsahara-Handel zwischen Tschad und Libyen. Dissertation, Universität zu Köln https://kups.ub.uni-koeln.de/3263/1/DissertationMeerpohl.pdf

Mueller, P. A., & Oppenheimer, D. M. (2014). The pen is mightier than the keyboard: Advantages of longhand over laptop note taking. Psychological Science, 25, 1159–1168. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797614524581

Röttger-Rössler, B. & Seise, F. (2023). Tangible pasts: Memory practices among children and adolescents in Germany, an affect-theoretical approach. In Ethos 51 1–96-110. https://doi.org/10.1111/etho.12377

Röttger-Rössler, B., Scheidecker, G. & Lam A. T. A. (2019). Narrating visualized feelings: Photovoice as a tool for researching affects and emotions among school students. In Analyzing Affective Societies. Methods and Methodologies. (p. 78-97). London, New York: Routledge Studies in Affective Societies. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429424366

Sanjek, R. (Eds.). (1990). Fieldnotes: The Makings of Anthropology. Ithaca. Cornell University Press.

Tuma, R.; Schnettler, B. & Knoblauch, H. (2013). Videographie. Einführung in die interpretative Videoanalyse sozialer Situationen. Wiesbaden. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-531-18732-7

Wetzels, M. (2021). Affektdramaturgien im Fußballsport. Die Entzauberung kollektiver Emotionen aus wissenssoziologischer Perspektive. Bielefeld: transcript Verlag. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783839455081

Citation

Röttger-Rössler, B. (2023). Recording Formats and Strategies. In Data Affairs. Data Management in Ethnographic Research. SFB 1171 and Center for Digital Systems, Freie Universität Berlin. https://en.data-affairs.affective-societies.de/article/recording-formats-and-strategies/