Informed Consent

Definition

Informed consent refers to the research participants' agreement to the collection and processing of data and information related to them as part of a research project, as well as their voluntary participation based on comprehensive and understandable information. It is also required for potential data archiving and reuse. The informed consent must address both legal data protection requirements and ethical principles equally.

Introduction

In empirical research projects, it is generally necessary to obtain informed consent, which provides participants with detailed information about the research project and explicitly requests their approval. Consent can be obtained in either written or oral form. However, since there is a legal requirement to provide proof of consent, the written form is often recommended.

Informed consent serves multiple purposes: On the one hand, it is part of legal data protection requirements when processingThe term 'processing' is defined as 'any operation or set of operations which is performed on personal data or on sets of personal data, whether or not by automated means, such as collection, recording, organisation, structuring, storage, adaptation or alteration, retrieval, consultation, use, disclosure by transmission, dissemination or otherwise making available, alignment or combination, restriction, erasure or destruction;' (BlnDSG §31, 2020; EU GDPR Article 4 No. 2, 2016). Processing therefore refers to any form of working with personal data, from collection to erasure. Read More personal dataPersonal data includes: 'any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person (data subject); an identifiable natural person is one who can be identified, directly or indirectly, in particular by reference to an identifier such as a name, an identification number, location data, an online identifier, or to one or more factors specific to the physical, physiological, genetic, mental, economic, cultural, or social identity of that natural person(…)” (EU GDPR Article 4 No. 1, 2016; BDSG §46 para. 1, 2018; BlnDSG §31, 2020). Read More and protects the individual’s right to decide on the disclosure and use of their given information. Data protection and the protection of personal rights are therefore closely linked to aspects of anonymization or pseudonymization (see article Anonymization and Pseudonymization). On the other hand, it is an essential principle of research ethics and respects the autonomy and self-determination of research participants. The affected individuals are informed about the objectives and methodology of the research/study, as well as their rights and potential risks associated with participation. Based on this information, research participants can freely decide whether they wish to take part in the research project.

For social and cultural anthropologists, it is particularly relevant to avoid an ethnocentric perspective on research ethics and to adapt informed consent to the respective research context.

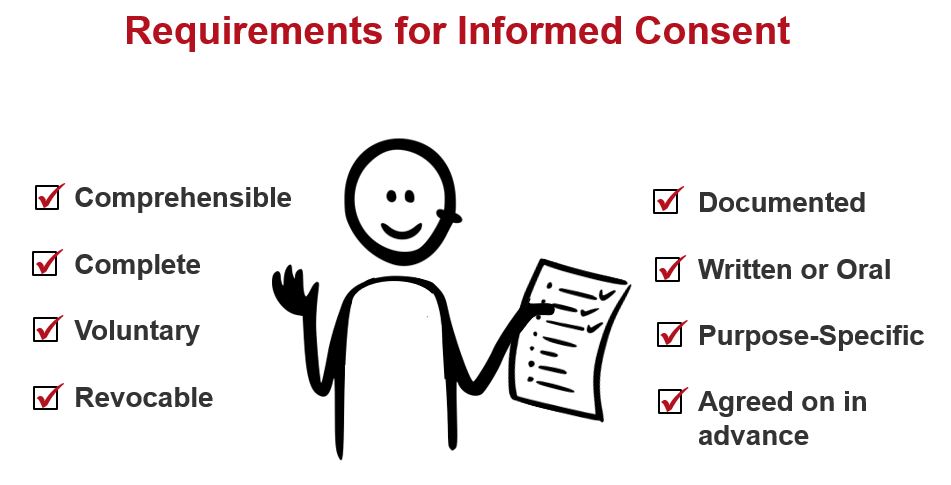

Requirements for a valid informed consent:

1) Information, Decision-Making Competence, and Capacity to Consent

To exercise their right to self-determination and assess the potential consequences of their consent, affected individuals must understand what they are confirming with their signature. Informed consent should therefore be transparent, comprehensible, and formulated appropriately for the respective target group, including all relevant information without overwhelming or deterring participants.

Linguistic, cultural, and/or age-related comprehension barriers must be considered to enable participants to make a genuinely informed decision. Furthermore, legal regulations regarding age of consent must be observed. In Germany, parental consent is required for minors up to the age of sixteen. In such cases, both the minors and their legal guardians must provide consent. For other national contexts, the legal age threshold for independent consent may vary (Verbund FDB, 2019).

2) Voluntariness

Informed consent is only valid if it is given voluntarily, without coercion or pressure. Research participants must be free to choose whether and to whom they allow data collection and processing. It is thus essential to inform the affected individuals that informed consent can be withdrawn or refused at any time. However, withdrawal only takes effect from the moment it is declared, as "data processing activities that have already taken place based on valid consent are not affected by withdrawal."1Translated by Saskia Köbschall. (Schaar, 2017, p. 6)

3) Purpose Specification

Informed consent is given by participants for one or more specific purposes, which should be "as specific as necessary and as general as possible."2Translated by Saskia Köbschall. (Verbund FDB, 2019, p. 6) This results in consent options that allow participants to decide whether their personal data may be made available beyond the current research project, e.g., for archiving and reuse. If the purposes of data processing change significantly during the research project (e.g., due to a new research question), a new, adapted consent must be obtained from the affected individuals. It is crucial to specify all steps of the intended data use and processing in a transparent, complete, and precise manner, as otherwise, restrictions or complications may arise in data use, archiving, or reuse.

It can be summarized as follows:

"Informed consent requires that study participants are made aware of the essential aspects of the research project, that their consent is given for a specific purpose, and that they have been informed that they may revoke their voluntarily given consent at any time".

(Trixa & Ebel, 2015, p. 12)3Translated by Saskia Köbschall.

Motivation

In qualitative social science research, particularly in ethnographic fieldworkIn scientific research processes, research data refers to all information collected both analog and digital. In social and cultural anthropology, research data is mostly, though not exclusively, gathered through stationary fieldwork and is methodologically characterized by participant observation. This means that data is purposefully generated through social interactions, observation, and interviews, and does not exist independently of the personal and affective interactions between researchers and participants. Therefore, in ethnographic fieldwork, one cannot speak of collecting pre-existing raw data; rather, data is processually created during research and must be understood as constructed. Read More, it is essential to consider ethical and legal guidelines, including those related to informed consent. Since empirical field research is collaborative, reciprocal, and based on trust, collected data are often personal and sensitive. Therefore, researchers must carefully weigh the consequences of their actions and ensure the protection of both research participants and themselves from any potential harm.

"Empirical sciences often explore areas that are legally sensitive in terms of data protection. They deal with confidential, personal, and protected information about individuals. ... For any ethically responsible research, it is therefore essential to develop and implement a strategy for protecting the identity of study participants".

(Trixa & Ebel, 2015, p. 12)4Translated by Saskia Köbschall.

The protection of research participants must be taken into account when processing research data and materials and when using them, for example, in publications and presentations, as well as when sharing them for reuse. What is required by research ethics has a corresponding legal basis in data protection law: According to the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the data protection laws of the federal states, the consent (informed consent) of the affected persons must generally be obtained for the collection, deletion, or possible reuse of collected data..

According to the GDPR, particularly sensitive dataWithin the category of personal data, there is a subset known as special categories of personal data. Their definition originates from Article 9(1) of the EU GDPR (2016), which states that these include information about the data subject’s: Read More includes information on origin, political views, religious affiliation, and data on health or sexuality, as the processing of this information may pose a risk to the fundamental rights and freedoms of the affected persons. Data of this kind may only be collected with the explicit consent of the participants and must also be "specifically addressed in a consent declaration if they are collected within the research project or transferred to a research data center for archiving and secondary use" (Kretzer et al., 2020, p. 2).

Methods

Source: Informed Consent, Anne Voigt with CoCoMaterial, 2023, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

Timing and Form

Consent should ideally be obtained before data collection and should be acquired either in written form, through a signature on a form, or orally, with appropriate documentation.

Although written consent has the advantage of being legally binding and verifiable, it does not necessarily guarantee an ethically appropriate and responsible dissemination of information. It may also be perceived by research participants as too formal or even intimidating, potentially leading to misunderstandings or discomfort. Additionally, obtaining written consent is practically impossible in some cases, such as when research participants are illiterate or when written bureaucratic processes are entirely uncommon in the given research context (see Practical Examples).

If oral consent is coherently and legally documented and verifiable (for example, as a recorded and retrievable confirmation on a recording device), it serves as an effective alternative to written consent. In certain fields and research contexts, it may even facilitate better understanding and establish a stronger trust relationship between researchers and participants:

"Recorded oral consent on audio or even on video tape combined with oral explanations may replace a signed form."

(Huber & Imeri, 2021, p. 16)

To ensure that an oral consent declaration meets data protection requirements, it is advisable to consult with the data protection officers of the respective institution5The data protection officer of FU Berlin can be found at: https://www.fu-berlin.de/en/einrichtungen/interessenvertretungen/datenschutz/dahlem/index.html.

The form of documentation (whether written or oral) should be adapted to the specific research context and negotiated consensually with the involvement of research participants:

"Every single case needs its own strategy for negotiating consent".

(Huber & Imeri, 2021, p. 13)

Contents

The following three components should ideally be included in informed consent to ensure its legal and substantive completeness and effectiveness (Verbund FDB, 2019; Imeri et al., 2023, p. 235):

1) Information about the Research Project

- Introduction to the research project – details on content, process, and objectives

- Methods of data collection (e.g., questionnaires, video recording, photography, conducting interviews, participant observation, etc.)

- Names of the participating research institutions

2) Data Protection and Rights

- Information on key rights related to participation, as well as data processing and sharing, particularly regarding voluntariness and the right to withdraw, limit processing, or object without any disadvantages

- Possibility of revocation with effect for the future

- Information on which personal data (e.g., names, address details, age) and, if applicable, special categories of personal data under the GDPR will be collected and processed

- Identity of those responsible and the data processing entities

- Purposes, objectives, and details on the intended processing and use (e.g., dissertation to be published); if archiving and reuse are planned, these should be explicitly mentioned

- Notes on the type of processing, if already known (e.g., transcription, planned anonymization procedures, etc.)

- Reference to the confidential handling of personal data: for example, separate storage of contact and research data

- Information on how research data will be stored, preserved, and used in the long term

3) Consent Form

- Confirmation of consent, name, location/date, signature

Practical Examples

The following examples describe specific contexts from ethnographic research fields and discuss the impact that different approaches to informed consent have had on research practice.

Example 1: Informed Consent in the Context of Long-Term Ethnographic Field Research (Röttger-Rössler, 2023)

As audio file, only in German

Source: Commentary on Informed Consent Röttger-Rössler, Birgitt Röttger-Rössler, 2023, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

As transcript

A large part of ethnographic research takes place within the framework of long-term, stationary field stays and is characterized by close participation of researchers in the daily life of the respective group. In this "classic" research format, "informed consent" becomes relevant on two levels: a formal and an informal level.

First, every ethnographer usually requires an official, governmental research permit to even be allowed to stay on-site for an extended period. The complexity of regulations varies by country. In Indonesia, for example, a research permit must be obtained from the state research authority to even qualify for a long-term research visa. The approval process is based on a research proposal that must be submitted in advance, and the decision can take a long time and even be denied. Some politically sensitive topics make it nearly impossible to obtain a research permit.

Once the research permit is obtained, it must be presented to regional authorities and officials. The approval process follows the descending order of bureaucratic hierarchy: at the lowest level are local officials such as district and regional leaders or village heads, who ultimately bear everyday responsibility for the researchers authorized by higher authorities. Typically, these local officials take on the role of informing the community about the goals and content of the research project, often in collaboration with the researcher.

Is this practice to be understood as "informed consent"? In hierarchically structured societies, the local population is not asked for their opinion or explicit approval – they are merely informed.

This was precisely the case in our research in South Sulawesi, Indonesia. The kepala kampung (literally: "head of the village") gathered the villagers in the place where my husband and I intended to live and conduct research for a year. He explained that we were there with official permission from the highest authorities in Jakarta to write a book about the village and that everyone should strive to ensure that we only wrote positive things.

It was a highly ambivalent situation. We attempted to explain our specific research interests in more detail but quickly realized that our academic presentation of research concerns was entirely out of place and meant nothing to the villagers. Handing out pre-prepared forms and requesting written consent would have been completely impossible, not only due to the high illiteracy rate but also because of deep mistrust toward official documents.

Did we therefore conduct research without "informed consent"? No – because, in the following weeks and months, we were constantly questioned by people about who we were and what we wanted. We explained our intentions repeatedly and gradually learned how to articulate them in a clear, non-academic way.

By allowing us into their lives over time and gradually involving us more in their daily activities, the villagers expressed their consent – or rather, practiced it. The local people always had full control over what they chose to share with us and what they did not. Only during later research stays did I realize how much had initially been kept from us.

This, in my opinion, is a crucial point: if people do not agree with the research goals, the researcher’s personality, or their behavior, they will find ways to resist and boycott the research. In everyday research situations, the local population is continuously reminded of the researcher’s presence and interests – whether through their constant note-taking in field journals, their many questions about seemingly obvious matters, or their clueless and often awkward behavior in various situations.

In short: In the context of long-term, stationary field research, "informed consent" does not come in the form of a signed document – it takes place in everyday practice. However, this means that ethnographic "informed consent" eludes formalized documentation standards.

This example illustrates, on the one hand, that "informed consent" can be understood as a research practice that unfolds repeatedly in the daily interactions between the researcher and the research participants. From an ethical perspective, this frequently practiced form of informed consent is not objectionable. However, it cannot be documented in a formalized way and, therefore, cannot be verified. On the other hand, this example highlights that formal (written or recorded oral) consent is entirely uncommon in some contexts and can appear highly unfamiliar to the local population, potentially leading to distrust and significantly complicating research.

Example 2: Limits and Challenges of Informed Consent (Dilger, 2005)

As audio file, only in German

Source: Commentary on Informed Consent Dilger, Camilla Heldt, 2023, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

As transcript

Between 1995 and 2006, Hansjörg Dilger (Professor of Social and Cultural Anthropology at Freie Universität Berlin) conducted research on HIV/AIDS, morality, and social relationships in rural and urban Tanzania. The research focused on the living conditions of infected and ill individuals and the organization of support and assistance from their familial, social, and/or religious networks. This ethnographic long-term study in Tanzania lasted a total of 13 months (Dilger, 2005, pp. 24).

One notable aspect of the research funding application process was that the German Research Foundation (DFG) did not consider any ethical aspects in its review. It was only when applying for a research permit in the host country, Tanzania, that Dilger was required to obtain ethical approval. The application was forwarded to a local medical institution (NIMR), which categorized the research as public health research with a health-oriented focus. Consequently, the ethical guidelines for health science research were applied. Dilger, who considered his research to be classic socio-anthropological work, was initially surprised by this classification.

However, bureaucratic ethical guidelines reached their limits in actual fieldwork, particularly concerning the process of obtaining informed consent, as Dilger himself describes: “In all these situations, I quickly realized that it would have been ethically indefensible to directly ask my interview partners about HIV/AIDS – or to present them with a written informed consent form that explicitly mentioned HIV/AIDS” (Dilger, 2015).

In rural Tanzania, HIV/AIDS is highly stigmatized both socially and culturally, often being associated with witchcraft, (sexual) moral transgressions, social or ritual violations by the infected individuals (Dilger, 2009, pp. 109). Here, it is essential to overcome the ethnocentric biomedical perspective on "disease" and to integrate alternative ways of thinking (Dilger, 2015) about “witchcraft, rumors, viruses, and spirits” (ibid.) as explanations for illness.

Directly questioning people about HIV infections or AIDS diagnoses could have been interpreted as an ethically problematic accusation, which, according to Dilger, would have been unacceptable: “In rural areas, I instead approached the topic by asking about "serious" and "chronic" illnesses and how individuals and family networks dealt with such challenges” (Dilger, 2015). This allowed his interview partners and himself to discuss the core questions of the research project in a meaningful way – one that was determined by the participants themselves (ibid.).

This example shows that obtaining informed consent is ethically contested and is not always possible or appropriate. Specific ethical questions arise individually in each research project, requiring consideration of whether the research itself may cause harm. The (e.g., psychological, moral, or physical) protection and integrity of research participants must always be ensured. As illustrated in this example, these questions are particularly relevant when dealing with taboo topics such as sexuality, death, or illness. In such cases, not only the signing of a consent form but even mentioning the research topic or project title can pose a risk and/or hinder trust-building and field access. Dilger reflects retrospectively: "Would my research participants have always agreed to talk with me if I had immediately informed them about my study's connection to HIV/AIDS (even if they later opened up about this topic on their own)?" (Dilger, 2015).

The necessity of informed consent, as well as the ethical standardization, institutionalization, and resulting obligations imposed by ethics committees, is a topic of discussion not only in ethnology. In Germany, overarching ethical standards for ethnographic research are (still) not the norm. However, researchers in the USA, for example, are required to obtain a positive ethics review due to the Institutional Review Boards (IRB). This is critical because "particularly politically and socially sensitive topics would hardly stand a chance of receiving ethical approval for ethnographically flexible research approaches if ethical criteria were applied rigidly." (Dilger, 2015).

Thus, while ethical standards can constrain and hinder the research process, they also impose significant challenges for researchers. Nonetheless, ethical guidelines should be known and considered, particularly for research stays abroad and interdisciplinary projects.

Ultimately, as Dilger states, "ethnology - also in dialogue with other disciplines - must engage in proactive discussions on how our field can shape the inevitable institutionalization of ethical standards and values while simultaneously not regressing from the theoretical and conceptual debates of the past decades." (Dilger, 2015).

Example 3: Advantages of Written Informed Consent (Inhorn, 2004)

As audio file, only in German

Source: Commentary on Informed Consent Inhorn, Camilla Heldt, 2023, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

As transcript

The 15-year research conducted by Marcia Inhorn on in-vitro fertilization (IVF) in private hospitals in Egypt and Lebanon from the late 1980s to the early 2000s demonstrates how obtaining written informed consent can have a positive impact on research processes and relationships.

During Inhorn’s research, gaining access to the medical-anthropological field proved to be challenging. Hospitals in both countries in the late 1980s were affected by privatization and patronage structures, making ethnographic research nearly impossible without contact with a medical "gatekeeper". Additionally, IVF and infertility (both male and female) were culturally stigmatized and highly sensitive issues, strictly kept confidential.

For anthropologists, especially given the politically conflict-laden situation in the Middle East, gaining access to this sensitive research field was particularly difficult.

However, Inhorn was able to gain access to private hospitals in Lebanon and Egypt through contacts with medical gatekeepers who informed their patients about the research topic and introduced the researcher to them. For this, she obtained the standardized ethics approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB).

This ethics approval proved highly beneficial given the particularly sensitive topic of in-vitro fertilization. The written consent form - which provided information about the research objectives and emphasized the voluntary nature of participation - along with formal signed consent, helped establish trust among the research participants.

Through this formalization process, participants could be certain that their interviews would be conducted with strict confidentiality.

„In my view, the informed consent process was crucial in reassuring women that what they told me would be held in the strictest confidence, and that their names would never be used in any published report … I would argue that the process of written informed consent may actually ´break the ice´ and lead to greater rapport when the topic being discussed is private, sensitive, or illegitimate/illega. (….) Using written informed consent forms to guarantee secrecy has worked to my advantage (….) Indeed, several women in my study commented after our interviews were finished, ´Now I´ve told you all my secrets“ (…) as long as I assure women of that privacy through the written informed consent process, they were more than willing to share their stories of suffering with me (Inhorn, 2004, p. 2099).

This example illustrates that obtaining (written) informed consent can, in some cases, be beneficial and relevant to the ethnographic research process. Particularly in subject areas affected by stigmatization, written consent assures participants of the confidential handling of sensitive research data. This can foster trust in researchers and serve as an initial "icebreaker."

Thus, the written form of informed consent does not necessarily have to be intimidating or discouraging. It is often unavoidable in medical anthropology settings, such as institutional environments like hospitals, where bureaucratic procedures are common.

It becomes evident that researchers must continuously engage with the specific conditions and structures of their research field, as well as the security and comfort of participants, to create an environment where they feel safe and at ease sharing their experiences, perspectives, and stories. In such contexts, written informed consent can be a supportive tool.

Discussion

Informed consent is a crucial instrument in research data management, legitimizing data processing, the use of research data for publications, as well as their archiving and sharing. In the ethnological context of ethnographic research, informed consent – understood as a “formal, inflexible, pre-obtained, and documented written declaration for both research and data archiving” (Imeri, 2018, p. 75) – is often met with skepticism.

This skepticism arises because informed consent is subject to both ethical and formal regulatory processes within empirical research. In the Anglo-American context, obtaining informed consent is institutionally and mandatorily reviewed and assessed by ethics committees and is considered a fundamental principle of research ethics. In cultural and social anthropology in the German-speaking world, ethics reviews are not yet mandatory; however, considerations regarding the effectiveness of informed consent have gained importance since the introduction of the GDPR in May 2018.

Nevertheless, ethnographic research presents profound challenges and issues concerning the highly formalized requirement of obtaining informed consent (see Practical Example Röttger-Rössler). One major concern is that the necessity of obtaining informed consent before conducting research could negatively affect the openness of the research projectAn attitude of methodological openness is essential in ethnographic research to adapt to the dynamics of social processes and respond to unforeseen events in the field. A fixed, unchangeable set of research methods does not meet these requirements. Furthermore, ethnographic research is also characterized by openness toward research materials after data collection; this approach encourages the continuous establishment of new theoretical perspectives on the material in order to allow for constructive and multi-layered interpretations. Read More and process. In most cases, it is impossible to provide comprehensive information in advance about the specific research project, including its exact course, research questions, objectives, and anticipated results. As a result, informed consent in ethnographic research remains inherently incomplete – "in process" and "unfinished" (Benner & Löhe, 2019, p. 352).

Additionally, due to the openness of the ethnographic field, unplanned and spontaneous encounters and interactions frequently occur, making it impossible to obtain informed consent before engaging with research participants. The boundaries of actual research participation are, therefore, highly fluid. Consequently, consent is often understood and practiced as a "continuous task and a dynamic-reflective negotiation process”6Translated by Saskia Köbschall. (Imeri, 2018, p. 74). This raises questions about which form of consent – written or oral – is suitable for participation in research as well as for the potential archiving of research data. The question remains whether alternative or more flexible consent regulations and formats are necessary to meet data protection requirements while minimizing negative impacts on ethnographic research processes.

Informed consent is particularly criticized for potentially granting the researcher exclusive rights and control over research data through a signed document, even though knowledge in ethnographic research is shared, jointly generated, and thus considered co-produced. Therefore, data ownership and control should not reside solely with researchers or research institutions. On the other hand, informed consent can also serve as a tool to grant research participants some degree of control over their data by allowing them to participate in decisions regarding the reuse of their personal data. However, this is only feasible in contexts where local actors understand and are interested in the digital storage and reuse of data.

Moreover, the formal and official process of obtaining consent poses significant challenges for ethnographic researchers, particularly in the simultaneous process of trust-building. It is crucial to recognize that ethnographic research generally involves the establishment of reciprocal, intensive, and often long-term relationships based on trust. Obtaining formal informed consent can disrupt interaction processes in the field and permanently damage relationships with research participants - especially when the research topic is heavily stigmatized in the local context (see Practical Example Dilger). When dealing with sensitive or highly taboo subjects such as illness, debt, or violence, a strong foundation of trust is essential. The format of consent - ideally written and signed - may, in some cases, create additional distrust among certain groups who are already exposed to repression, making access to the field more difficult or even impossible. However, in contexts where formalized practices such as signing documents are common, obtaining written informed consent can positively influence research relationships (see Practical Example Inhorn).

Researchers are personally responsible for handling data and research materials ethically throughout the project and beyond. This responsibility raises ethical concerns that extend beyond simply avoiding tangible harm and disadvantages for participants as outlined by the GDPR. The relationship and interaction between researchers and research participants – along with associated vulnerabilities or power asymmetries – must not be overlooked in discussions of research ethics, risk assessment, and harm prevention. Research involving vulnerable or marginalized groups (e.g., individuals in situations of illegality, violence, or criminality) must carefully consider the potential risks that obtaining written consent may pose for both participants and researchers.

Thus, ethical considerations do not end with obtaining informed consent; they should be integrated into every phase and decision-making process until the research report is finalized. In this regard, it is essential to critically assess whether informed consent genuinely serves to uphold ethical research principles:

“It is the quality of the consent, not the format, that is relevant”.

(Huber & Imeri, 2021, p. 14)

In summary, informed consent is generally a legal necessity and an ethical obligation in empirical research projects. However, as the preceding discussion illustrates, the requirement to obtain informed consent as mandated by the GDPR presents a series of methodological and ethical challenges – particularly within ethnographic research practice. There are no simple or universally applicable solutions that can be directly adopted from textbooks and standardized. Each research project must individually determine whether, when, and in what form effective informed consent can be obtained. This includes balancing the need to protect participants’ rights with the goal of enabling future data archiving and reuse.

From a research data management perspective, it is advisable to document all activities and decisions related to informed consent in the data management planA data management plan (DMP) describes and documents the handling of research data and materials during and after the project period. The DMP specifies how data and materials are generated, processed, stored, organized, published, archived, and, if applicable, shared. Additionally, it outlines responsibilities and rights. As a 'living document' (a dynamic document that is continuously revised and updated), the DMP is regularly reviewed and adjusted as needed throughout the course of the project. Read More (DMP). If obtaining informed consent is impossible or does not meet legal requirements, it is recommended to document the reasons for this in the DMP.

Tools

- Research Data Centre (RDC) Qualiservice provides GDPR-compliant templates for informed consent on its website. The individual sections can be adapted to the specific requirements of your project. The guidelines on informed consent explain how to use these templates and outline the legal framework. https://www.qualiservice.org/de/helpdesk.html#downloads

- Verbund Forschungsdaten Bildung. (2018a). Formulierungsbeispiele für „informierte Einwilligungen“. Version 2.1 (fdbinfo 4). Forschungsdaten-bildung.de. https://doi.org/10.25656/01:22301

This document offers wording templates for informed consent forms, including both optional and mandatory text elements. These templates incorporate the three essential components of informed consent: (1) Informations section, (2) Data protection notice, (3) Consent declaration. - Verbund Forschungsdaten Bildung. (2018b). Formulierungsbeispiele für „informierte Einwilligungen" in leichter Sprache. Version 1.1 (fdbinfo 5). Forschungsdaten-bildung.de. https://doi.org/10.25656/01:22302

Templates for informed consent forms in easy-to-understand language, including both optional and mandatory text elements. These templates incorporate the three essential components of informed consent: (1) Informations section, (2) Data protection notice, (3) Consent declaration. - Verbund Forschungsdaten Bildung. (2019). Checkliste zur Erstellung rechtskonformer Einwilligungserklärungen mit besonderer Berücksichtigung von Erhebungen an Schulen. Version 2.0 (fdbinfo 1). Forschungsdaten-bildung.de. https://doi.org/10.25656/01:22297

Checklist as guide for structuring consent declarations. - Kretzer, S., Mozygemba, K., Heuer, J.-O. & Huber, E. (2020). Erläuterungen zur Verwendung der von Qualiservice bereitgestellten Vorlagen für die informierte Einwilligung. Unter Mitarbeit von Universität Bremen. Qualiservice Working Papers 2. https://doi.org/10.26092/ELIB/192

The Research Data Centre (RDC) Qualiservice provides detailed explanations on obtaining informed consent. At the end of the document, three different consent forms are available: (1) Consent for the (primary) research project (page 10), (2) Consent for further use of personal data (secondary use) (page 18), (3) Consent for archiving (page 26).

Templates are also available in English and can be used as a guide, e.g., for obtaining oral consent.

Notes

- 1Translated by Saskia Köbschall.

- 2Translated by Saskia Köbschall.

- 3Translated by Saskia Köbschall.

- 4Translated by Saskia Köbschall.

- 5The data protection officer of FU Berlin can be found at: https://www.fu-berlin.de/en/einrichtungen/interessenvertretungen/datenschutz/dahlem/index.html

- 6Translated by Saskia Köbschall.

Literature and References

Benner, A. & Löhe, J. (2019). Die informierte Einwilligung auf Tonband: Analyse im Rahmen einer qualitativen Interviewstudie mit älteren Menschen aus forschungsethischer und rechtlicher Perspektive. Zeitschrift Für Qualitative Forschung, 20(2), 341-356. https://elibrary.utb.de/doi/epdf/10.3224/zqf.v20i2.08

Dilger, H. (2005). Leben mit Aids. Krankheit, Tod und soziale Beziehungen in Afrika. Eine Ethnographie. Campus.

Dilger, H. (2017). Ethics, Epistemology and Ethnography: The Need for an Anthropological Debate on Ethical Review Processes in Germany. Sociologus, 67 (2), 191–208. https://doi.org/10.3790/soc.67.2.191

Europäische Datenschutz-Grundverordnung. (EU-DSGVO, 2016). Verordnung (EU) 2016/679 des Europäischen Parlaments und des Rates vom 27. April 2016. intersoft consulting. https://dsgvo-gesetz.de

Huber, E. & Imeri, S. (2021). Informed consent in ethnographic research: A common practice facing new challenges (preprint), Qualiservie Working Papers Nr. 4-2021. http://dx.doi.org/10.26092/elib/1070

Imeri, S. (2018). Archivierung und Verantwortung. Zum Stand der Debatte über den Umgang mit Forschungsdaten in den ethnologischen Fächern. In RatSWD Working Paper Nr. 267/201, 69–79. https://doi.org/10.17620/02671.35

Inhorn, M. C. (2004). Privacy, privatization, and the politics of patronage: ethnographic challenges to penetrating the secret world of Middle Eastern, hospital-based in vitro fertilization. Social Science & Medicine, 59(10), 2095–2108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.03.012

Kretzer, S., Mozygemba, K., Heuer, J.-O., Huber, E. (2020). Erläuterungen zur Verwendung der von Qualiservice bereitgestellten Vorlagen für die informierte Einwilligung. Unter Mitarbeit von Universität Bremen, Qualiservice Working Papers, Nr. 2. https://doi.org/10.26092/elib/192

Schaar, K. (2017). Die informierte Einwilligung als Voraussetzung für die (Nach-)Nutzung von Forschungsdaten: Beitrag zur Standardisierung von Einwilligungserklärungen unter Einbeziehung der Vorgaben der DSGVO und Ethikvorgaben. RatSWD Working Paper, Nr. 264. https://doi.org/10.17620/02671.12

Trixa, J. & Ebel, T. (2015). Einführung in das Forschungsdatenmanagement in der empirischen Bildungsforschung. Zusammenfassung des Workshops im Rahmen des CESSDA-Trainingsprogramms. forschungsdaten bildung informiert, Nr. 2. https://doi.org/10.25656/01:21969

Verbund Forschungsdaten Bildung. (FDB, 2019). Checkliste zur Erstellung rechtskonformer Einwilligungserklärungen mit besonderer Berücksichtigung von Erhebungen an Schulen (2nd. ed.). fdbinfo, Nr.1. https://doi.org/10.25656/01:22297

Citation

Heldt, C. & Röttger-Rössler, B. (2023). Informed Consent. In Data Affairs. Data Management in Ethnographic Research. SFB 1171 and Center for Digital Systems, Freie Universität Berlin. https://en.data-affairs.affective-societies.de/article/informed-consent/