Anonymization and Pseudonymization

Definition

Anonymization and pseudonymization are often used synonymously, but the two terms should be distinguished:

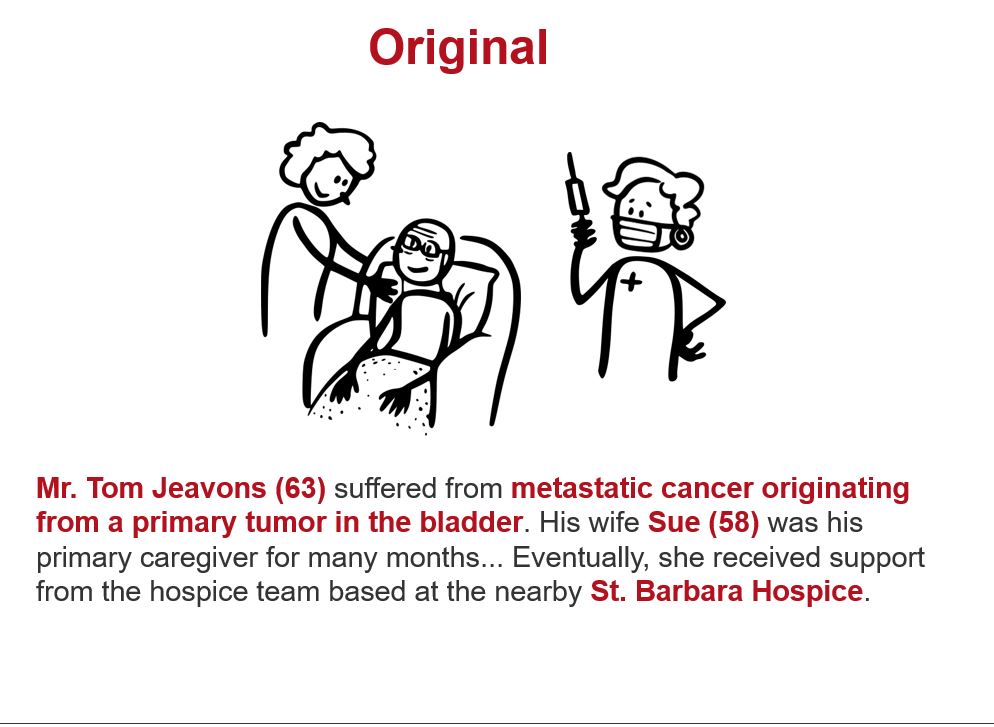

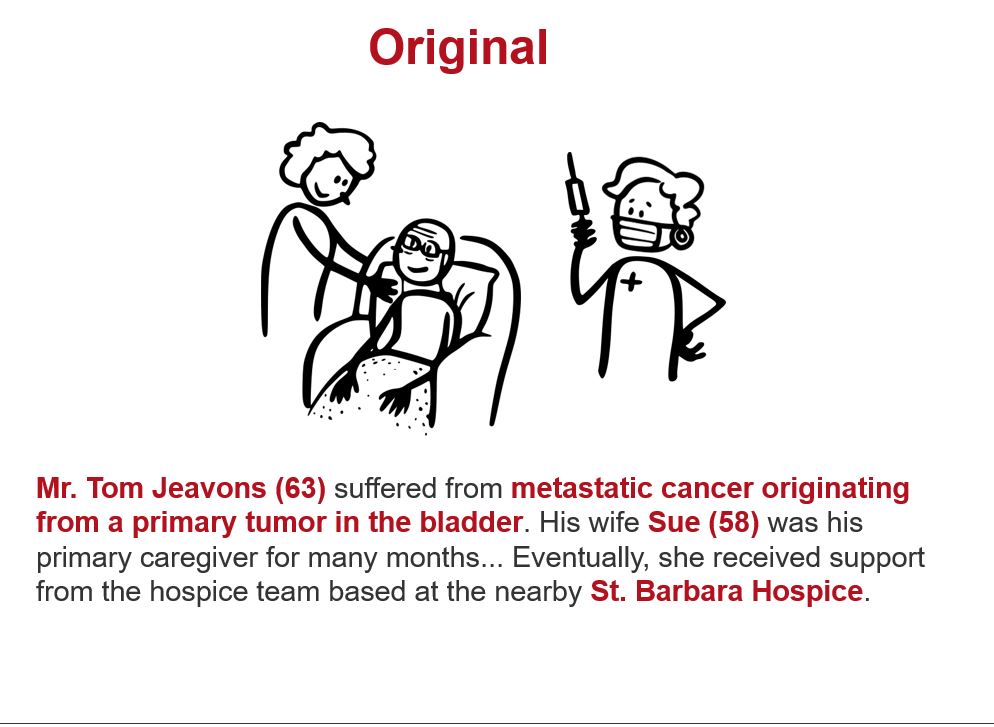

1) Anonymization

Derived from the Greek word for "namelessness," anonymization refers to the alteration of personal dataPersonal data includes: 'any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person (data subject); an identifiable natural person is one who can be identified, directly or indirectly, in particular by reference to an identifier such as a name, an identification number, location data, an online identifier, or to one or more factors specific to the physical, physiological, genetic, mental, economic, cultural, or social identity of that natural person(…)” (EU GDPR Article 4 No. 1, 2016; BDSG §46 para. 1, 2018; BlnDSG §31, 2020). Read More in such a comprehensive way that it is either impossible or only feasible with disproportionate effort to trace the data back to the individual. The core of anonymization involves the irrevocable deletion of information about affected individuals - research partners and any third parties - so that re-identification and de-anonymization are prevented or at least significantly hindered. Once data has been anonymized, it is no longer considered personal data and is no longer subject to GDPR regulations.

2) Pseudonymization

Pseudonymization also involves replacing, altering, or describing personal identifiers during data processing in such a way that the data subjects cannot be directly re-identified without additional information. In contrast to anonymization, however, identifying features such as names and addresses are not destroyed or deleted but are separated from the dataset and stored securely. This means that the personal references remain traceable and the persons concerned can still be re-identified in the case of pseudonymous data, unlike anonymous data.

The legal distinction between pseudonymization and anonymization lies in the ability to link the data back to individuals via a separate key file in the former case, whereas such linkage is impossible in the latter (Imeri, Klausner & Rizolli, 2023, p. 244).

It is essential that anonymization and pseudonymization processes are tailored to each research project and adapted to the specific field conditions and purposes of these methods. By employing creative pseudonymization strategies adapted to local contexts, ethnographers can provide thick descriptions of the living conditions they study.

A special form of pseudonymization is fictionalization, where personal data is replaced, supplemented, or narratively restructured with fictional elements to protect individuals' rights.

Introduction

In social and cultural anthropology, research typically involves the collection of personalPersonal data includes: 'any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person (data subject); an identifiable natural person is one who can be identified, directly or indirectly, in particular by reference to an identifier such as a name, an identification number, location data, an online identifier, or to one or more factors specific to the physical, physiological, genetic, mental, economic, cultural, or social identity of that natural person(…)” (EU GDPR Article 4 No. 1, 2016; BDSG §46 para. 1, 2018; BlnDSG §31, 2020). Read More and sensitiveWithin the category of personal data, there is a subset known as special categories of personal data. Their definition originates from Article 9(1) of the EU GDPR (2016), which states that these include information about the data subject’s: Read More data, which must be protected in accordance with the European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Anonymization or pseudonymization removes personal identifiers from data, thereby making its further processing for publication, archivingArchiving refers to the storage and accessibility of research data and materials. The aim of archiving is to enable long-term access to research data. On one hand, archived research data can be reused by third parties as secondary data for their own research questions. On the other hand, archiving ensures that research processes remain verifiable and transparent. There is also long-term archiving (LTA), which aims to ensure the usability of data over an indefinite period of time. LTA focuses on preserving the authenticity, integrity, accessibility, and comprehensibility of data. Read More, and reuseData reuse, often referred to as secondary use, involves re-examining previously collected and published research datasets with the aim of gaining new insights, potentially from a different or fresh perspective. Preparing research data for reuse requires significantly more effort in terms of anonymization, preparation, and documentation than simple archiving for storage purposes. Read More lawful – provided that the affected individuals have not explicitly consented to the non-anonymized processing and sharing of their personal data.

For social and cultural anthropologists, the legal requirements of the GDPR (see also the article on Data Protection) often present a dilemma when weighed against the need to maintain precision, authenticity, and academic freedom. Altering personal identifiers can result in the loss of critical information that is essential for the utility of the data within the project and beyond. Depending on the research question, factors such as gender, age, social position, occupation, religious or political affiliation, etc., may not be substitutable without distorting key social relationships. This tension – between providing a dense and transparent account of research processes and findings, while also respecting the social and personal positioning of the ethnographer in the field, and ensuring the necessary protection of participants and their personal rights – requires context-specific and situation-specific solutions.

The anonymization concept employed by the Qualiservice Research Data CenterThe Research Data Centre (RDC) Qualiservice provides qualitative social science data for scientific reuse. Accredited in 2019 by the German Council for Social and Economic Data (RatSWD), it adheres to their quality assurance criteria. In addition to data reuse, researchers have the option to share and organize their own research data, with the Qualiservice team offering advisory support. Qualiservice is committed to the DFG guidelines for ensuring good scientific practice and also adheres to the FAIR Guiding Principles for Scientific Data Management and Stewardship as well as the OECD Principles and Guidelines for Access to Research Data from Public FundingFor further informationen see also: https://www.qualiservice.org/en/. Read More, for example, replaces sensitive information with sociologically relevant descriptors to protect individuals while maximizing the scientific-analytical use and reuse value of the data. For instance, specific place names are not replaced with "City A" or "City B" but with "Residency A" or "Large City in Southern Germany." Corresponding strategies of abstraction should be individually adapted to the field- and material-specific requirements and conditions.

Motivation

The necessity to anonymize or pseudonymize personal data arises from ethical and legal data protection requirements (GDPR). Responsibility and loyalty towards research participants oblige researchers ethically and morally to handle and protect personal data responsibly and in consultation with participants. In particular, sensitive dataWithin the category of personal data, there is a subset known as special categories of personal data. Their definition originates from Article 9(1) of the EU GDPR (2016), which states that these include information about the data subject’s: Read More – such as information on sexual orientation, political views, or ethnic origin – may pose significant risks, including political and security-related threats for participants if published, depending on the research situation and context. These circumstances call for meticulous anonymization and pseudonymization strategies. Additionally, it is legally mandated to ensure the "protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of their personal dataThe term 'processing' is defined as 'any operation or set of operations which is performed on personal data or on sets of personal data, whether or not by automated means, such as collection, recording, organisation, structuring, storage, adaptation or alteration, retrieval, consultation, use, disclosure by transmission, dissemination or otherwise making available, alignment or combination, restriction, erasure or destruction;' (BlnDSG §31, 2020; EU GDPR Article 4 No. 2, 2016). Processing therefore refers to any form of working with personal data, from collection to erasure. Read More" (GDPR, 2016, Article 1) and not to endanger their well-being, safety, and freedom. Violating this regulation can have criminal consequences (e.g., research participants can press charges against data that was published against their will).

However, it should also be noted that research participants may, in some cases, explicitly wish to be identified by name and other identity characteristics in publications or presentations (see interview with A. von Poser). Nevertheless, even such cases require a careful consideration of the pros and cons.

The decision to pseudonymize personal data or intentionally retain identifiable characteristics should be negotiated in consultation with participants and, ideally, documented in a written or oral informed consent agreementInformed consent refers to the agreement of research participants to take part in a study based on the basis of comprehensive and understandable information. The design of an informed consent must address both ethical principles and data protection requirements. Read More (see the article on Informed Consent).

Methods

Researchers in disciplines that employ ethnographic methods must fundamentally address questions of pseudonymization, as "qualitative researchers typically focus on sensitive topics that are reconstructed from the subjective perspectives of respondents. Thus, the very personal details and individual references, institutions, organizations, and third parties that need to be anonymized are at the heart of the research" (Kretzer, 2013, p. 21Translated by Saskia Köbschall.).

A common practice in social and cultural anthropology is to replace personal names with pseudonyms when writing up research results (Imeri, Klausner & Rizzolli, 2023, p. 243) – for example, changing "Marta" to "Barbara" – and, if necessary, modifying other identifying characteristics to protect research participants or third parties mentioned in the material. However, the latter is not always straightforward. For instance, it is not always feasible to replace or omit the name of a significant office, but by mentioning it, the respective office holder at the time of the research can be identified.

A common strategy in social and cultural anthropologyis to further obscure specific research locations by using fictitious place names, often without explicitly specifying the research regions. Additionally, methods and strategies of fictionalization are used in the field, wherein personal information is replaced, supplemented, or narratively transformed with fictional elements to protect research participants. Through creative pseudonymization adapted to local conditions, ethnographers can still provide a dense description of the living conditions they study.

However, it is seldom acknowledged that, while these strategies effectively prevent the identification of individuals by outsiders – such as readers of publications or users of archived datasets – they often fail to conceal identities within the communities being studied. This is particularly true in the case of extended case studiesThe Extended Case Method (ECM) was developed in British social anthropology during the 1950s and 1960s and has become one of the standard qualitative methods in the field. It can be defined as the detailed documentation and analysis of specific events or event sequences observed in the field, from which general theoretical principles can be derived. Unlike a singular, time-limited case study, the ECM investigates the interconnectedness of multiple social events over extended periods, where the same actors are involved. This method allows for the capture of social negotiation processes. ECM data typically consist of 'thick descriptions' that contain numerous sensitive personal references, which require particularly careful protection and anonymization. Read More, which are often used to reconstruct complex sequences of events. In such cases, even if personal and place names are pseudonymized, those involved typically know who the respective protagonists were. Ethnographers must therefore approach the preparation and presentation of case studies with particular care and sensitivity. Careful fictionalization often remains the only means to ensure data protection in these instances. Pseudonymization and anonymization are therefore not merely mechanical procedures, but rather complex and creative processes.

Moreover, pseudonymization is difficult to implement "on the run" during the ethnographic documentation process, since ethnographers typically work with the real names of their research participants in observation protocols (which later serve as the basis for reconstructing complex case histories during analysis). This practice is tied to the fact that personal names are strong identifiers, greatly facilitating ethnographers' orientation within their material, whereas using pseudonyms during the documentation process tends to create significant distance. Most social and cultural anthropologists therefore pseudonymize their data material only prior to publication or when preparing it for archives. This means, however, that they must store their primary material with heightened security measures (see the article on Data Protection).

Dealing with multimedia data (images, audio, video) poses a particular challenge, as such data are difficult to pseudonymize or anonymize. Consequently, data protection must be handled with extreme care in these cases (see interview with M. Kramer). Research Data Centre (RDC) Qualiservice addresses this issue by significantly restricting access to multimedia data containing personal references, allowing access only on-site in Bremen. For photographs, blurring or pixelating faces has become a common practice in publications; for audio data, voices can be distorted, although this often results in an unpleasant sound. Overall, such distortion techniques significantly impair the informational value of visual and audio documents, although they remain indispensable in certain contexts.

Particular attention must be paid to issues of anonymization and pseudonymization, especially in light of the growing importance of social media content in ethnographic research.

Tips and Tools

There are various software tools for anonymization and pseudonymization (e.g., IQDA Qualitative Data Anonymizer or eAnonymizer) which can automatically pseudonymize data such as transcribed interviews during their creation. It is recommended that only excerpts of interviews be published in pseudonymized form, to prevent third parties from reconstructing complete contexts.

A particularly useful tool is QualiAnon, an anonymization tool developed as open-source software by the Research Data Centre (RDC) Qualiservice in Bremen (Nicolai et al., 2021). QualiAnon supports the anonymization/pseudonymization of text data. As open-source software, it is freely available for researchers to use2For further information, see the QualiAnon User Manual (Nicolai & Mozygemba, 2023)..

The German Network of Educational Research Data also provides helpful guidance and examples of distortion strategies (Meyermann & Porzelt, 2014).

Practical Examples

The following examples from ethnographic practice illustrate the challenges and limitations of pseudonymization in the field and during publication, while showcasing how researchers navigate these issues.

Example 1: Pseudonymization, Bodner (2018)

In his monograph "Berg/Leute. Ethnografie eines ausgebliebenen Bergsturzes am Eiblschrofen bei Schwaz in Tirol 1999" (Mountain/People: Ethnography of a Near-Miss Rockslide at Eiblschrofen near Schwaz in Tyrol 1999), European ethnologist Reinhard Bodner explores how local residents manage the risks associated with rockslides. The monograph provides detailed insights into the author’s methodological approach in the field, particularly regarding anonymization and pseudonymization strategies. For most of his interview participants, the author refrains from using their real names to protect their privacy, opting instead for pseudonyms or aliases. He explains his approach as follows:

"I avoided phonetic similarities to real first and last names; however, by using family names that are relatively common in Schwaz, I sought to retain (or recreate) a local tone" (Bodner, 2018, p. 623Translated by Saskia Köbschall.).

For instance, Franz Müller was not transformed into Max Müller, Mr. X, or the initials FM. Instead, the pseudonymization process was approached as a creative endeavor, striking a balance between protecting personal rights and preserving the informational value of the data. As a result, participants in the publication are given names such as Richard Fuhrmann or Ingrid Zoller.

Public figures, such as the mayor, retain their real names in the monograph and are not pseudonymized. For particularly prominent individuals, such as a spokesperson for a citizens' initiative who is frequently featured in the media, the author omits their first and last names but mentions their social function. This example highlights the significant role pseudonymization plays in shaping ethnographic representation. Through the pseudonymization process, ethnographers actively shape the portrayal of field actors, influencing how these individuals are perceived by readers. By emphasizing certain characteristics of research participants while omitting others, ethnographers create “figures of their own reality” (Bodner, 2018, p. 62), a dynamic researchers must remain aware of.

Example 2: Fictionalization, Rottenburg (2002)

An illustrative example of extensive fictionalization can be found in the book „Weit hergeholte Fakten. Eine Parabel der Entwicklungshilfe“ (2002, Far-Fetched Facts: A Parable of Development Aid) by social anthropologist Richard Rottenburg. In this work, Rottenburg employs literary abstraction to present the findings of his research on development cooperation in an African context.

Rottenburg constructs the narrative through four distinct authorial voices. He himself appears as the empirical author only in the introduction and the final chapter. The second voice is that of the ethnographer Eduard B. Drotleff, who narrates the first three parts of the book, detailing his field research. Additionally, two other narrators contribute their perspectives: an organizational ethnologist and a local entrepreneur. Each voice embodies a different role and viewpoint, illustrating various facets of the research context.

This literary technique allows Rottenburg to highlight the constructed nature of the text. He justifies his choice of fictionalization by arguing that naming real-life individuals could lead readers to fixate on the question, “Who is actually responsible for the described circumstances?” Instead, fictionalization is intended to shift focus away from the strengths and weaknesses of individual actors, directing attention to the broader significance of structural principles (Rottenburg, 2002, p. 4).

Example 3: Anonymization through Animation, Gregory Gan (2023)

“Empathy for Concrete Things” is an animated documentary released in 2023 by Gregory Gan. The film explores the history of concrete, panel-block architecture (Plattenbau) through case studies of major 20th-century art movements and dialogues with five visual artists. These artists share their experiences of living and working in Soviet-era concrete, panel-block apartments. By interweaving personal and global narratives, the film critiques the utopian fantasies of modernity and Cold War imagery against the backdrop of current humanitarian and political crises.

To ensure participants’ anonymity while creatively interpreting their narratives, the film employs original watercolor animations. These artistic visuals replace direct representations of the participants’ identities. Additionally, interviews were carefully edited to remove all identifying information and re-recorded with voice actors4These measures are rather atypical for visual anthropology projects, as participants are usually visible in videos. However, they were ethically and legally necessary here because some of the statements were politically sensitive..

Source: Trailer for "Empathy for Concrete Things", Gregory Gan, 2023, All rights reserved

Example 4: Anonymization through Aggregation, Asher & Jahnke (2013)

The article “Curating the Ethnographic Moment” (Asher & Jahnke, 2013) discusses challenges and practices in research data management, particularly concerning ethics, obtaining informed consent, and strategies for anonymization and pseudonymization. Researchers were interviewed about their experiences. A sociologist describes the following dilemma:

“I wanted to do life histories with priests [in central Pennsylvania], and part of the problem was ... we got into a situation where people might tell me things about their personal lives that are sort of not confidential in the IRB sense but that might be upsetting to their congregations - like I talked to one priest who had been married three times, where if the congregation had known about that they would have been very upset. There’s nothing illegal about it; this person’s not shy about telling that, but it could have been damaging.” (2-13-111411).

This excerpt contains a reference to the research location, "central Pennsylvania." A reader of the article left the following comment on the website:

“I am finding this article to be extremely useful and interesting. However, I noticed this “I wanted to do life histories with priests [in central Pennsylvania]” and I think you should remove the geographic reference. There can’t be that many priests in central Penn. and marriage certificates are public records. By including this geography in your article, you may yourself be compromising the privacy of the potential respondents”.

The authors responded with the following justification:

“Your point is well taken. We chose to replace a specific geographic reference (in this case a town) with the more general and nonspecific “central Pennsylvania” in order to retain contextual information while expanding the population of potential people to a large enough degree to make identification difficult. Since “central Pennsylvania” can be used to refer to almost anywhere between Philadelphia and Pittsburgh, it would take a very committed person to compile a list of priests and cross reference it with marriage records–both very difficult tasks, especially since the person in question could have been married anywhere. However, as an added precaution, we have also omitted information about when the researcher was conducting this work and denomination of the priest the researcher was discussing, which further expands the population that would have to be investigated. We therefore believe the risk of identification is very low, but you are correct in noting that researchers and archivists need to be aware that seemingly innocuous details can result in breaches of confidentiality.“

This example illustrates the delicate balance researchers must strike when attempting to anonymize sensitive information while retaining enough context to ensure the integrity and interpretability of their research. It also highlights the ongoing vigilance required to assess and mitigate risks to participant confidentiality, even when aggregating or generalizing potentially identifying details.

Discussion

Open Questions:

- How much socially and scientifically relevant information is lost through distortion strategies, and to what extent can fictionalized and distorted data still be meaningfully reused?

- Is it always possible to anticipate which information might pose a risk to research participants in the future? “We don’t know if the anonymization strategies in place now will still hold up twenty years from now, and […] what kind of information from my field might later be politically weaponized” (Behrends et al., 2022, p. 85Translated by Saskia Köbschall.).

- In many cases, anonymity cannot be guaranteed, as “the overall structure of personal information itself – that is, its individually specific context, for example, within the reconstruction of an individual biography – can theoretically allow re-identification despite the anonymization of detailed information” (Kretzer, 2013, p. 36Translated by Saskia Köbschall.). How can this be dealt with?

- It must also be considered that officially issued and archived research permits may enable the reconstruction of ethnographers’ identities as well as their research locations. How secure are pseudonymization strategies in such cases?

- The ongoing digitization process makes achieving anonymity increasingly difficult and requires careful consideration of field recording strategies (see interview with M. Kramer; Shklovski & Vertesi, 2013; Bachmann et al., 2017). Are secure forms of anonymization and pseudonymization still achievable in digitally networked worlds?

Tools

Practical support for anonymizing and pseudonymizing qualitative research data is offered by:

- The anonymization tool QualiAnon for semi-automated anonymization of text-based data:

https://www.qualiservice.org/de/helpdesk/webinar/tools.html - The accompanying guide by Mozygemba and Hollstein (2023):

User Manual: QualiAnon – Tool for the anonymization of text data (v1.3)

Notes

- 1Translated by Saskia Köbschall.

- 2For further information, see the QualiAnon User Manual (Nicolai & Mozygemba, 2023).

- 3Translated by Saskia Köbschall.

- 4These measures are rather atypical for visual anthropology projects, as participants are usually visible in videos. However, they were ethically and legally necessary here because some of the statements were politically sensitive.

- 5Translated by Saskia Köbschall.

- 6Translated by Saskia Köbschall.

Literature and References

American Anthropological Association. (AAA, 2004). Statement on Ethnography and Institutional Review Boards. Adopted by AAA Executive Board. American Anthropological Association. Advancing Knowledge, Solving Human Problems. https://www.americananthro.org/ParticipateAndAdvocate/Content.aspx?ItemNumber=1652

Asher, A. & Jahnke, L. M. (2013). Curating the Ethnographic Moment. Archive Journal. http://www.archivejournal.net/essays/curating-the-ethnographic-moment/

Bachmann, G., Knecht, M. & Wittel, A. (2017): The Social Productivity of Anonymity. Introduction. In: Ephemera: Theory & Politics in Organization 17/2, 241–258. https://irep.ntu.ac.uk/id/eprint/31952/1/PubSub9418_Wittel.pdf

Behrends, A.; Knecht, M.; Liebelt, C.; Pauli, J.; Rao, U.; Rizzolli, M.; Röttger-Rössler, B.; Stodulka, T. and Zenker, O. (Eds.) (2022). Zur Teilbarkeit ethnographischer Forschungsdaten. Oder: Wie viel Privatheit braucht ethnographische Forschung? Ein Gedankenaustausch. SFB 1171 ‚Affective Societies‘ Working Paper Nr. 01/22. http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/refubium-35157.2

Bodner, R. (2018): Berg/Leute. Ethnografie eines ausgebliebenen Bergsturzes am Eiblschrofen bei Schwaz in Tirol (1999). Dissertation.

Europäische Datenschutz-Grundverordnung. (EU-DSGVO, 2016). Verordnung (EU) 2016/679 des Europäischen Parlaments und des Rates vom 27. April 2016. intersoft consulting. https://dsgvo-gesetz.de

Imeri, S., Klausner, M. & Rizzolli, M. (2023). Forschungsdatenmanagement in der ethnografischen Forschung. Eine praktische Einführung. In Kulturanthropologie Notizen 85, S. 223–254. https://doi.org/10.21248/ka-notizen.85.22

Kretzer, S. (2013): Arbeitspapier zur Konzeptentwicklung der Anonymisierungs-/Pseudonymisierung in Qualiservice. Open Access Repository. https://www.ssoar.info/ssoar/handle/document/47605

Laurie, H. & Gush, K. (2019). Understanding Couples‘ Experiences of Job Loss in Recessionary Britain: a Linked Qualitative Study, 2008-2013: Special Licence Access. [data collection]. UK Data Service. SN: 7657. http://doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-SN-7657-1

Meyermann, A. & Porzelt, M. (2014). Hinweise zur Anonymisierung qualitativer Daten. Frankfurt am Main : DIPF | Leibniz-Institut für Bildungsforschung und Bildungsinformation. (forschungsdaten bildung informiert; 1). https://doi.org/10.25656/01:21968

Mozygemba, K. & Hollstein, B. (2023). Anonymisierung und Pseudonymisierung qualitativer textbasierter Forschungsdaten – eine Handreichung. Qualiservice Working Papers, 5. Bremen. Forschungsdatenzentrum Qualiservice. https://doi.org/10.26092/elib/2525

Nicolai, T. & Mozygemba, K. (2023). QualiAnon User Manual, v1.3. Qualiservice Technical Report 2-2023. Bremen. https://doi.org/10.26092/elib/2576

Nicolai, T. , Mozygemba, K., Kretzer, S. & Hollstein, B. (2021). QualiAnon – Qualiservice Tool for Anonymizing Text Data (version 1.0.1). Qualiservice. University of Bremen. https://github.com/pangaea-data-publisher/qualianon

Rottenburg, R. (2002). Weit hergeholte Fakten: Eine Parabel der Entwicklungshilfe. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter Oldenbourg. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110508505

Shklovski, I. & Vertesi, J. (2013). Un-Googling Publications. The Ethics and Problems of Anonymization. In CHI’13 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems 2169–2178. ACM Digital Library. https://doi.org/10.1145/2468356.2468737

Additional Literature

Antes, A. L., Walsh, H. A., Strait, M., Hudson-Vitale, C. R. & DuBois, J. M. (2018). Examining Data Repository Guidelines for Qualitative Data Sharing. Journal of empirical research on human research ethics: JERHRE, 13(1), 61–73. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5953419/

Lenk, C., Duttge, G., Fangerau, H. (Eds.) (2014): Handbuch Ethik und Recht der Forschung am Menschen. Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

Marnau, N. (2016). Anonymisierung, Pseudonymisierung und Transparenz für Big Data. Datenschutz Datensicherheit – DuD, 40, 428–433. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11623-016-0631-9

Schaar, P. (2014). Anonymisieren und Pseudonymisieren als Möglichkeit der Forschung mit sensiblen, personenbezogenen Forschungsdaten. In: Lenk, Christian; Duttge, Gunnar; Fangerau, Heiner (Eds.) Handbuch Ethik und Recht der Forschung am Menschen (95-100). Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

Citation

Heldt, C. & Röttger-Rössler, B. (2023). Anonymization and Pseudonymization. In Data Affairs. Data Management in Ethnographic Research. SFB 1171 and Center for Digital Systems, Freie Universität Berlin. https://en.data-affairs.affective-societies.de/article/anonymization-and-pseudonymization/