Archiving

Definition

Archiving refers to the controlled, secure, and long-term preservation of documents and data in analog or digital storage locations (archives, repositories) to make them available for further (scientific) reuse.

Introduction

The term “archive“ (from the Latin archivum, meaning “filing cabinet“) often conjures images of dusty basement rooms filled with endless rows of shelves stacked with files. For institutions like government agencies, which require the documentation and retention of administrative processes (e.g., insurance companies, health and pension funds, registry offices), this image is certainly accurate, although digitizationDigital data are created through digitalization, which involves converting analog materials into formats suitable for electronic storage on digital media. Digital data offer the advantage of being easily and accurately duplicated, shared, and machine-processed. Read More is increasingly becoming the norm.

But in addition to administrative archives, there exists a vast variety of archives, both public and private, which serve as repositories of collective memory. These institutions - like museums, libraries, and documentation centers - often hold significant societal value. Scientific collections across various disciplines represent a specialized form of archives, which are primarily maintained for research purposes. The Wissenschaftliche Sammlungen (Scientific Collections) portal offers insights into the diversity of these collections. Of particular interest are ethnological collections housed at universities in Göttingen, Frankfurt, Mainz, Tübingen, Marburg, Hannover, and others, which include artifacts, as well as audio, visual, film, and written documentation1 see: https://portal.wissenschaftliche-sammlungen.de.

The Open Science movement’sSince the early 2000s, the Open Science movement has advocated for an open and transparent approach to science in which all stages of the scientific knowledge process are made openly accessible online. This means that not only the final results of research, such as monographs or articles, are shared publicly, but also materials that accompanied the research process, such as lab notebooks, research data, software used, and research reports. This approach aims to promote public participation in science and knowledge, engaging interested audiences. It also seeks to encourage creativity, innovation, and new collaborations, while enabling the verification of findings in terms of quality, accuracy, and authenticity – a process intended to democratize research. Components of Open Science include Open Access and Open Data, which provide the infrastructure for sharing interim research results. Read More call to make research data as accessible as possible for scientific reuseData reuse, often referred to as secondary use, involves re-examining previously collected and published research datasets with the aim of gaining new insights, potentially from a different or fresh perspective. Preparing research data for reuse requires significantly more effort in terms of anonymization, preparation, and documentation than simple archiving for storage purposes. Read More and public interest connects with a longstanding tradition of preparing and storing documents and objects for research and public information purposes. Many scientific collections grant access to their archives for interested parties and even publicly exhibit parts of their collections.

This article focuses exclusively on making digital and digitized data accessible through institutional archives or repositoriesA repository is a storage location for academic documents. In online repositories, publications are digitally stored, managed, and assigned persistent identifiers. Cataloging facilitates the search and use of publications and author information. In most cases, documents in online repositories are openly and freely accessible (Open Access). Read More2This does not necessarily mean that the material is freely accessible on the internet; access may be controlled or restricted as needed., rather than on the individual archiving practices of researchers who store their data and materials in personal digital folders or physical boxes. The ultimate aim of archiving research data is usually to enable their reuse (see article on data reuse). A crucial aspect of this process is data documentation in the form of metadata, which makes the data discoverable, comprehensible, and usable by others (see article on data documentation and metadata).

Motivation

Institutional factors and personal responsibilities are often cited as key motivators for researchers to archive their data. Archiving is often in the interest of fundersFunding institutions are organizations that provide financial support for scientific research, such as foundations, associations, or other entities. Internationally, most of these institutions have established guidelines for research data management (RDM) in research projects, meaning that potential funding is tied to specific requirements and expectations for handling research data. Some of the most well-known funding institutions in German-speaking countries include the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF), the education and science ministries of the federal states, the German Research Foundation (DFG), the Volkswagen Foundation, the Austrian Science Fund (FWF), and the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNF). Read More and institutions that financially support the research. Access to archived data allows third parties to conduct follow-up research with new questions or comparative studies, potentially resulting in new research perspectives. Furthermore, existing data can be used as example materials in teaching, particularly in methodological training.

Many researchers also feel personally responsible for archiving their data, recognizing its potential historical significance. Research data can document local ways of life that often no longer exist in the same form as they did at the time of the research.

Methods

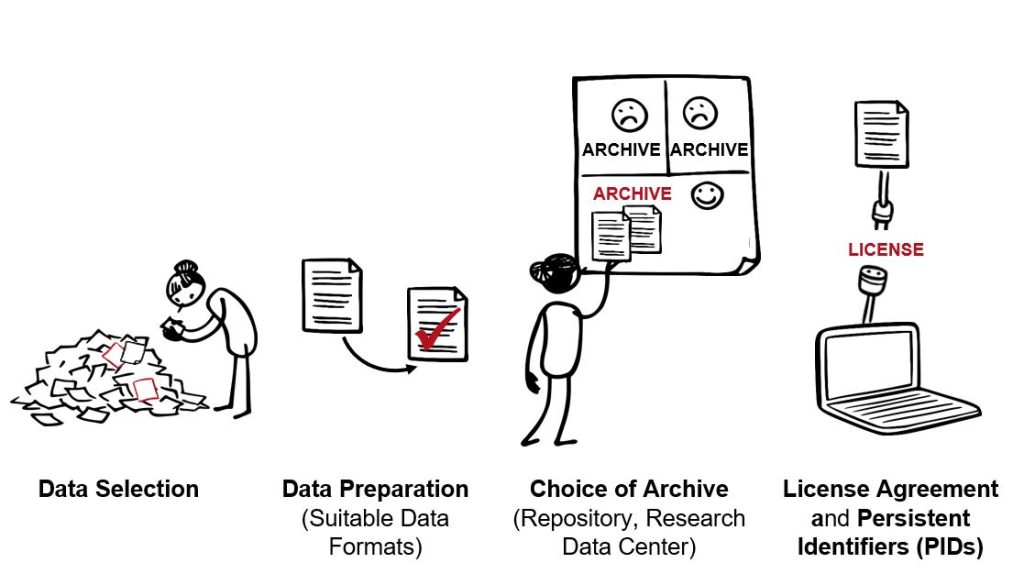

Source: Archiving, Anne Voigt with CoCoMaterial, 2023, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Data Selection

Archiving research data rarely involves sharing complete material corpora. Instead, it requires a thoughtful approach to determine what can and should be shared (DGSKA, 2015).

A significant challenge in archiving ethnographic data is the sensitive nature of the content. Social and cultural anthropologists often collect data on sensitive topics, the archiving of which in public repositoriesA repository is a storage location for academic documents. In online repositories, publications are digitally stored, managed, and assigned persistent identifiers. Cataloging facilitates the search and use of publications and author information. In most cases, documents in online repositories are openly and freely accessible (Open Access). Read More could pose unpredictable (political) risks or consequences for the research participants. These data must be treated with the utmost care and in adherence to ethical research principles (see the article on Data Protection). Additionally, obtaining informed consent from participants for archiving identifiable personal dataPersonal data includes: 'any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person (data subject); an identifiable natural person is one who can be identified, directly or indirectly, in particular by reference to an identifier such as a name, an identification number, location data, an online identifier, or to one or more factors specific to the physical, physiological, genetic, mental, economic, cultural, or social identity of that natural person(…)” (EU GDPR Article 4 No. 1, 2016; BDSG §46 para. 1, 2018; BlnDSG §31, 2020). Read More is essential but can often prove extremely difficult in practice (see articles on Informed Consent and Anonymization).

Another challenge arises from the researcher's own involvement with their material, which often includes elements and references to the researcher themselves. Archiving such data for potential reuseData reuse, often referred to as secondary use, involves re-examining previously collected and published research datasets with the aim of gaining new insights, potentially from a different or fresh perspective. Preparing research data for reuse requires significantly more effort in terms of anonymization, preparation, and documentation than simple archiving for storage purposes. Read More means researchers may inadvertently disclose aspects of their personality, experiences, and positionality in the field to unknown third parties. This could conflict with the protection of their own personal rights unless they undertake the labor-intensive task of removing all personal elements from the data. However, such efforts often result in significant decontextualization.

These considerations underscore the need for careful deliberation on whether and under what conditions data archiving and reuse by third parties can be permitted, ensuring the protection of both the participants and the researchers. The central question in this regard is: for which potential users and purposes should researchers prepare which parts of their data, and in what form (Behrends et al., 2022, p. 17)?

For example, does the audience consist of:

- Academic audiences and professional peers in Germany, the country of research, or internationally, who are interested in the data from a scholarly perspective?

- State research agencies or local organizations, which may seek access to the data but could hold economic or political interests divergent from those of the researchers?

- Non-academic audiences interested in the research topic or whose interest researchers hope to cultivate, aiming to make the research accessible and visible beyond academic discourse, in line with the principles of Open Science'Open Science encompasses strategies and practices aimed at making all components of the scientific process openly accessible and reusable on the internet. This approach is intended to open up new possibilities for science, society, and industry in handling scientific knowledge” (AG Open Science, 2014, translation by Saskia Köbschall). Read More?

The decision regarding which data and materials can be made accessible, and under what conditions, should always be left to the researchers themselves, especially since they are personally involved in their respective fields and embedded in social relationships. The question of sharing data is therefore often linked to affective ties and loyalties, making it far from easy to resolve.

"Imagine, for example, an anthropologist, who investigates land right conflicts and therefore talks to the plantation owners – some of whom use illegal methods to expand their lands – and to local nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) that try to fight them, as well as to the ancestral owners of the land who have been cultivating it for generations, but who, in turn, also distrust the NGOs. Probably the anthropologist will be little inclined to share his or her information with the plantation owners, but possibly with the NGOs whose political commitment and mission he or she supports. The decision to share data with the NGO activists might on the other hand violate the trust of the ancestral land users, with whom the anthropologist feels particularly connected. But besides this, can anthropologists ever be sure to see through the motivations of their various interaction partners?"

(Rizzolli & Röttger-Rössler, 2024, p. 286)

This quote illustrates that the demand to share data with local research participants may sound straightforward but is often extremely difficult to implement and ethically challenging. The group of research participants is neither easy to define nor homogeneous.

Archives, Repositories, and Research Data Centers (RDCs)

Archives and repositoriesA repository is a storage location for academic documents. In online repositories, publications are digitally stored, managed, and assigned persistent identifiers. Cataloging facilitates the search and use of publications and author information. In most cases, documents in online repositories are openly and freely accessible (Open Access). Read More for qualitative data that account for the outlined aspects in their infrastructural organization – where trained personnel with experience in qualitative or ethnographic social research can provide specialized and discipline-specific consulting – remain scarce in Germany. An appropriate infrastructure for archiving and providing qualitative data is needed that ensures both the protection of data through secure, reliable and sustainable IT infrastructure and – as far as possible – access to the data material under controlled conditions and ideally in exchange with primary researchers (e.g. on-site use) (Imeri, 2017; Imeri et al., 2018; Eberhard, 2018; Eberhard, 2020).

A data service operating on this model and dedicated exclusively to qualitative research data is the Research Data Centre (RDC) QualiserviceThe Research Data Centre (RDC) Qualiservice provides qualitative social science data for scientific reuse. Accredited in 2019 by the German Council for Social and Economic Data (RatSWD), it adheres to their quality assurance criteria. In addition to data reuse, researchers have the option to share and organize their own research data, with the Qualiservice team offering advisory support. Qualiservice is committed to the DFG guidelines for ensuring good scientific practice and also adheres to the FAIR Guiding Principles for Scientific Data Management and Stewardship as well as the OECD Principles and Guidelines for Access to Research Data from Public FundingFor further informationen see also: https://www.qualiservice.org/en/. Read More at the University of Bremen. Qualiservice offers support and guidance to researchers during all phases of the research process. The center specializes in archiving qualitative and, particularly, ethnographic research materials with sensitive content, such as observation protocols, field notes, interviews, photographs, audio recordings, as well as audiovisual or internet-based data. It provides opportunities for archiving and enabling the scientific reuse of qualitative data. Researchers determine when and under what conditions data reuse is permissible3Qualiservice offers various options for this: examples include temporary embargoes (access restrictions for a set period) or the exclusion of specific uses, such as prohibiting the material’s use in teaching. For particularly sensitive data, it can be stipulated that access is allowed only on-site in Bremen..

Assigning Licenses and Persistent Identifiers

In research data centers such as Qualiservice, data providers can determine, via a license or corresponding data usage agreement, how access to their research data is granted and what usage rights are stipulated. The usage terms depend, among other factors, on whether personal and sensitive data have been processed and appropriate permissions have been obtained. Reuse, such as for research or teaching purposes via Qualiservice, must be explicitly authorized through informed consentInformed consent refers to the agreement of research participants to take part in a study based on the basis of comprehensive and understandable information. The design of an informed consent must address both ethical principles and data protection requirements. Read More from the affected individuals.

One of the most widely used licensing systems, especially for scientific articles, is the Creative Commons LicensesCreative Commons licenses are pre-formulated license agreements created by the non-profit organization Creative Commons, allowing copyright holders to grant public usage rights to their creative works. Once a work under a CC license is used by third parties according to the terms of the license, a contract is established (TUM, 2023, p. 5). Read More (Creative Commons, 2023b). The Creative Commons organization currently offers six pre-designed, standardized license agreementsIn a license agreement or through an open license, copyright holders specify how and under what conditions their copyrighted work may be used and/or exploited by third parties. Read More that copyright holdersThe German Copyright Act (UrhG) protects certain intellectual creations (works) and services. Works include literary works, photographic, film and musical works, as well as scientific or technical representations such as drawings, plans, maps, sketches, tables and plastic representations (§ 2 UrhG). The artistic, scientific achievements of persons or the investment made, on the other hand, are considered to be services worthy of protection (ancillary copyright).The author is entitled to publish and utilize the work. Read More can use to grant usage rights for their works. For scientific text publications, the CC-BY license has become the standard and is recommended by the German Research Foundation (DFG, 2014). Thanks to its modular, standardized structure, these licenses are easy to understand, even without legal expertise.

Research data and documentation intended for archiving should also be equipped with persistent identifiers (PIDs)A Persistent Identifier (PID) is a permanent digital code directly associated with a digital resource, such as a dataset, scholarly article, or other publication, making it permanently identifiable and findable. Unlike other serial identifiers (e.g., URLs), a Persistent Identifier refers to the object itself rather than its location on the internet. If the location of a digital object associated with a Persistent Identifier changes, the identifier remains the same; only the URL location in the identifier database needs to be updated or supplemented. This ensures that a dataset remains permanently findable, accessible, and citable (Forschungsdaten.info, 2023). Read More, which ensure the permanent findability and citability of the data. A PID is a durable reference to a digital resource, such as a dataset, that points to the object itself rather than its URL location. Even if the location of a digital object changes, the identifier remains the same (Forschungsdaten.info, 2023).

Currently, the most widely used persistent identifiers include the DOIDOI stands for Digital Object Identifier, a unique and permanent (persistent) identifier for digital objects, such as articles and contributions in scientific publications, as well as lecture publications and educational materials. A DOI must first be registered in the central database of the International DOI Foundation see: https://www.doi.org/. Read More and ORCIDAn example of a standardized identifier for uniquely identifying individuals is the ORCID (Open Researcher and Contributor ID). ORCID is an internationally recognized persistent identifier that allows researchers to be uniquely identified. The ID can be used by researchers for their scientific publications permanently and independently of any institution. It consists of 16 digits, grouped in four sets of four (e.g., 0000-0002-2792-2625). ORCID IDs are widely established in workflows at numerous publishers, universities, and research-related institutions and are often integrated into the peer-review process for journal articles An ORCID can be created free of charge at https://orcid.org/.. Read More:

- DOI (Digital Object Identifier): Refers to digital objects such as articles and contributions in scientific publications, as well as publications of lectures and educational materials.

- ORCID (Open Researcher and Contributor ID): Enables researchers and authors to be digitally referenced and uniquely identified.

Suitable File Formats for Archiving

The guidelines for good scientific practice stipulate a retention period of at least 10 years (GWP Guideline 17, 2022). In addition to ensuring the interpretability of the data through accompanying documentation and metadata (see article on Data Documentation and Metadata), it is important under the FAIR principlesThe FAIR Principles were first developed in 2016 by the FORCE11 community (The Future of Research Communication and e-Scholarship). FORCE11 is a community of researchers, librarians, archivists, publishers, and research funders aiming to bring about change in modern scientific communication through the effective use of information technology, thereby supporting enhanced knowledge creation and dissemination. The primary goal is the transparent and open presentation of scientific processes. Accordingly, data should be made findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable (FAIR) online. The objective is to preserve data long-term and make it available for reuse by third parties in line with Open Science and Data Sharing principles. Precise definitions by FORCE11 can be found on their website see: https://force11.org/info/the-fair-data-principles/. Read More to also guarantee their usability through appropriate file formatsThe terms 'file type' and 'file format' are often used interchangeably. A distinction is made between proprietary and open file formats. Proprietary formats usually require fee-based software to access, as they may not be compatible with other programs (e.g., PowerPoint for .ppt files or Photoshop for .psd files). In contrast, open formats such as .rtf or .png are based on standards and can be opened by many programs. Read More. Formats that require proprietaryProprietary file formats are file formats that cannot be opened or read by third parties, or only with difficulty, because they are protected by license or patent. In most cases, special (paid) software is required for this (Wikipedia, 2023). Examples include the Word format.docx or the Adobe Photoshop format.psd. Read More, often paid software such as Microsoft Office, MaxQDA, or Photoshop for processing are less suitable for archiving.

If such software is used in a research project, the data should be converted into more suitable file formats for archiving. Ideally, files to be archived should be "unencrypted, uncompressed, patent-free, and created in an open, documented standard" (Biernacka et al., 2021). Conversion can usually be carried out directly in the respective software during saving or using the export function.

Table: Recommended File Formats for Archiving (Biernacka et al., 2021)

| File Types | Recommendation | Avoid |

| Images | TIFF, JPEG2000, PNG | GIF, JPG |

| Text | TXT, HTML, RTF, PDF/A, DOCX | DOC, PDF |

| Tables | CSV, TSV, SPSS portable, XLSX | XLS, SPSS |

| Multimedia | Container: MPEG4, MKV Codec: Theora, Dirac, FLAC | QuickTime, Flash |

Discussion

As evident, several open questions remain regarding the archiving of data. Legal uncertainties, particularly in relation to copyrightThe German Copyright Act (UrhG) protects certain intellectual creations (works) and services. Works include literary works, photographic, film and musical works, as well as scientific or technical representations such as drawings, plans, maps, sketches, tables and plastic representations (§ 2 UrhG). The artistic, scientific achievements of persons or the investment made, on the other hand, are considered to be services worthy of protection (ancillary copyright).The author is entitled to publish and utilize the work. Read More, pose significant challenges and are not always straightforward to resolve (Wünsche et al., 2022, p. 27):

- Who owns the data when they are primarily generated through collaboration and communicative exchange?

- Who should be recognized as the author?

- Who decides how the research data will be managed going forward?

Another critical and unresolved issue is the multilingual nature of archives. Social and cultural anthropologists, in particular, often document their fieldwork in multiple languages, making archiving and reuse of such data significantly more complex:

- Which language should be used for archiving? Should it be the researcher’s native language? The language of the studied region (and thus accessible to the research participants), which would necessitate the availability of local repositoriesA repository is a storage location for academic documents. In online repositories, publications are digitally stored, managed, and assigned persistent identifiers. Cataloging facilitates the search and use of publications and author information. In most cases, documents in online repositories are openly and freely accessible (Open Access). Read More? Or should English, as the international language of science, be used? In any case, this would require substantial translation efforts, incurring considerable financial and time costs.

Considering these questions and the processes described earlier, we conclude that the decision about whether and which material should be archived must remain with each researcher, in consultation with their research participants, and should not be tied to funding conditions. Moreover, preliminary considerations and, if necessary, preparatory steps should already be integrated into the methodological approach and carried out in close collaboration with research participants.

Key aspects to be considered are:

- Preparing and selecting data for archiving and potential reuse.

- Determining which audience the data will address.

Ideally, the decision to archive data in appropriate repositories should be made prior to the empirical research, allowing for this aspect to be incorporated into data collection, and coordinated with the research participants, and resources for archiving can also be planned and applied for. However, in practice, this is rarely feasible, particularly in ethnographic research, as it is often not entirely clear in advance which areas will be investigated and to what extent the data - mindful of all data protection regulations and ethical considerations - will be suitable for archiving and reuse. Special care must be taken with sensitive dataWithin the category of personal data, there is a subset known as special categories of personal data. Their definition originates from Article 9(1) of the EU GDPR (2016), which states that these include information about the data subject’s: Read More to evaluate the extent to which data archives account for ethical considerations and ensure controlled access to datasets.

Tools

- Qualiservice: https://www.qualiservice.org/en/

- The Specialized Information Service for Social and Cultural Anthropology (FID SKA): Fachinformationsdienst SKAThe Specialized Information Service for Social and Cultural Anthropology (FID SKA) provides members of the German Society for Empirical Cultural Studies and the German Society for Social and Cultural Anthropology, as well as other interested researchers to a limited extent, with selected online resources for research. Read More serves as an infrastructure partner for ethnological disciplines, offering fundamental information and advisory services: https://www.evifa.de/en/research-data/research-data?set_language=en

- Guidelines for research data management and consultation options from Freie Universität Berlin: https://www.fu-berlin.de/en/sites/forschungsdatenmanagement/services/index.html

Examples of research data centers from other disciplines:

- DIW (German Institute for Economic Research): The FDZ-BO (Research Data Center for Business and Organizational Data) focuses on economic and social science contexts: https://www.diw.de/en/diw_01.c.623262.en/pages/data_services.html

- SOEP (Socio-Economic Panel): https://www.diw.de/de/diw_01.c.412809.de/sozio-oekonomisches_panel__soep.html

- Federal Statistical Office and statistical offices of the German states: https://www.destatis.de/EN/Service/_node.html

- Research Data Center (RDC) for Psychology: https://www.konsortswd.de/en/services/research/all-datacentres/fdz-zpid/

- GESIS (Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences): https://www.gesis.org/en/services/archiving-and-sharing

- PANGEA ® Data Publisher: https://www.pangaea.de/

- FDZ Bildung (Research Data Center for Education): https://www.fdz-bildung.de/home?la=en

- FDZ-AGD (Research Data Center for Spoken German at the Leibniz Institute for the German Language): https://www.konsortswd.de/en/services/research/all-datacentres/fdz-agd/

- RDC eLabour: An interdisciplinary center for qualitative research data from the sociology of work (eLabour): https://www.konsortswd.de/en/services/research/all-datacentres/fdz-elabour/

On FAIR Data

User-friendly English-language tools are available to evaluate the implementation of the FAIR principles in a dataset and provide guidance:

Notes

- 1

- 2This does not necessarily mean that the material is freely accessible on the internet; access may be controlled or restricted as needed.

- 3Qualiservice offers various options for this: examples include temporary embargoes (access restrictions for a set period) or the exclusion of specific uses, such as prohibiting the material’s use in teaching. For particularly sensitive data, it can be stipulated that access is allowed only on-site in Bremen.

Literature and References

Behrends, A.; Knecht, M.; Liebelt, C.; Pauli, J.; Rao, U.; Rizzolli, M.; Röttger-Rössler, B.; Stodulka, T. and Zenker, O. (Eds.) (2022). Zur Teilbarkeit ethnographischer Forschungsdaten. Oder: Wie viel Privatheit braucht ethnographische Forschung? Ein Gedankenaustausch. SFB 1171 ‚Affective Societies‘ Working Paper Nr. 01/22. http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/refubium-35157.2

Biernacka, K., Buchholz, P., Danker, S. A., Dolzycka, D., Engelhardt, C., Helbig, K., Jacob, J., Neumann, J., Odebrecht, C., Petersen, B., Slowig, B., Trautwein-Bruns, U., Wiljes, C. & Wuttke, U. (2021). Train-the-Trainer-Konzept zum Thema Forschungsdatenmanagement. (Version 4). Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5773203

Creative Commons. (2023b). Licenses List. Creative Commons. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/?lang=de

Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG). (2014). Appell zur Nutzung offener Lizenzen in der Wissenschaft. Information für die Wissenschaft Nr. 6. https://www.dfg.de/de/aktuelles/neuigkeiten-themen/info-wissenschaft/2014/info-wissenschaft-14-68

Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft. (DFG, 2022). Leitlinien zur Sicherung guter wissenschaftlicher Praxis. Kodex. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6472827

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Sozial- und Kulturanthropologie. (DGSKA, 2015). Positionspapier zum Umgang mit ethnologischen Forschungsdaten. Forschungsdaten Info. https://forschungsdaten.info/nachrichten/nachricht-anzeige/positionspapier-zum-umgang-mit-ethnologischen-forschungsdaten/

Eberhard, I. & Kraus, W. (2018). Der Elefant im Raum. Ethnographisches Forschungsdatenmanagement als Herausforderung für Repositorien. Mitteilungen der Vereinigung Österreichischer Bibliothekarinnen und Bibliothekare, 71(1), 41–52. DOI: 10.31263/voebm.v71i1.2018

Eberhard, I. (2020). Der Kontext bestimmt alles: Kontextdaten und Containerobjekte als Lösungsmöglichkeit für den Umgang mit sozialwissenschaftlichen qualitativen Daten. Erfahrungen aus dem Pilotprojekt „Ethnographische Datenarchivierung“ an der Universitätsbibliothek Wien. ABI Technik, 40(2), 169-176. https://doi.org/10.1515/abitech-2020-2007

Forschungsdaten.info. (2023). Glossar. forschungsdaten.info. https://forschungsdaten.info/praxis-kompakt/glossar/

Imeri, S. (2017): Open Data? Zum Umgang mit Forschungsdaten in den ethnologischen Fächern. In J. Kratzke & V. Heuveline (Ed.): E-Science-Tage 2017: Forschungsdaten managen (167-178). heiBOOKS. https://doi.org/10.11588/heibooks.285.377

Imeri, S., Sterzer, W., Harbeck, M. (2018). Forschungsdatenmanagement in den ethnologischen Fächern. Bericht aus dem Fachinformationsdienst Sozial- und Kulturanthropologie. Zeitschrift für Volkskunde, 114.1 (2018), 71–75.

Rizzolli, M. & Röttger-Rössler, B. (2024). Opening up ethnographic data. When the private becomes public. In Lünenborg, M. & Röttger-Rössler, B. (Eds). Affective Formation of Publics. Places, Networks, and Media (271-291). https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003365426-18

Wünsche, S., Soßna, V., Kreitlow, V. & Voigt, P. (2022). Urheberrechte an Forschungsdaten – Typische Unsicherheiten und wie man sie vermindern könnte. Ein Diskussionsimpuls. Bausteine Forschungsdatenmanagement. Empfehlungen und Erfahrungsberichte für die Praxis von Forschungsdatenmanagerinnen und -managern, Nr. 1/2022 (26-42). https://doi.org/10.17192/bfdm.2022.1.8369

Additional Literature

Bambey, D., Corti, L., Diepenbroek, M., Dunkel, W., Hanekop, H., Hollstein, B., Imeri, S., Knoblauch, H., Kretzer, S., Meier zu Verl, C., Meyer, C., Meyermann, A., Porzelt, M., Rittberger, M., Strübing, J., von Unger, H. & Wilke, R. (2018). Archivierung und Zugang zu Qualitativen Daten. RatSWD Working Paper Nr. 267/201. https://doi.org/10.17620/02671.35

Beer, B. & König, A. (Eds.).( 2020). Methoden ethnologischer Feldforschung. Ethnologische Paperbacks. (3rd ed.). Dietrich Reimer Verlag.

Corti, L., van den Eynden, V., Bishop, L., Woollard, M. (2019). Managing and sharing research data: A guide to good practice. (2nd ed.). SAGE.

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Volkskunde. (dgv, 2019). Positionspapier zur Archivierung, Bereitstellung und Nachnutzung von Forschungsdaten. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Empirische Kulturwissenschaft. https://www.dgekw.de/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/dgv-Positionspapier_FDM.pdf

Meyer, C., C. Meier zu Verl. (2018). Probleme der Archivierung und sekundären Nutzung ethnografischer Daten. In Bambey, D. et al. (Eds.). Archivierung und Zugang zu Qualitativen Daten. RatSWD Working Paper Series, Nr. 267/201, 80-89. https://doi.org/10.17620/02671.35

Stodulka, T. (2014). Feldforschung als Begegnung — Zur pragmatischen Dimension ethnographischer Daten. Sociologus, 64 (2), 179–205. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43645251

forschungsdaten.info. (2023c). Datenspeicherung und die Lebensdauer von Datenträgern. forschungsdaten.info. https://forschungsdaten.info/themen/veroeffentlichen-und-archivieren/formate-erhalten/

Citation

Heldt, C., Röttger-Rössler, B. & Voigt, A. (2023). Archiving. In Data Affairs. Data Management in Ethnographic Research. SFB 1171 and Center for Digital Systems, Freie Universität Berlin. https://en.data-affairs.affective-societies.de/article/archiving/